In the 18th canto of Dante’s Inferno, Dante and Virgil enter Malebolge, the eighth Circle of Hell. There, Dante sees sinners without number crossing back and forth on one of Malebolge’s bridges and compares the crowd to the throngs of jubilee pilgrims who passed across the bridge of the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome on their way to and from St. Peter’s Basilica.

Dante had been one of those pilgrims years before, when he and hundreds of thousands of other believers traveled to Rome for the Jubilee of 1300. That year, Pope Boniface VIII had issued a papal bull promising a plenary indulgence to all pilgrims who traveled to Rome, confessed their sins, and made daily visits to the basilicas of St. Peter and St. Paul. In the bull, Boniface alluded to past jubilees, describing jubilee as an ancient and venerable practice. But no other written record remains of those celebrations.

What does remain is a testimony even more ancient: God’s instructions to the Israelites in Leviticus 25:10:

“And you shall hallow the 50th year and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants; it shall be a jubilee for you, when each of you shall return to his property and each of you shall return to his family.”

The next 45 verses of Leviticus elaborate on those initial instructions, detailing how every 50 (or more accurately, 49 years), the Israelites were to return to the original owners any land that had been sold to pay debt, free those people who had sold themselves into slavery to pay off debts, and allow the land to lay fallow for a season.

“The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me to bring good tidings to the afflicted.”

A Levitical Law

This supernaturally given law, like others within the Levitical code, had a natural precedent.

According to Franciscan University theology professor Dr. John Bergsma, in some of the Gentile kingdoms of the day, a new king would call for something similar during the first year of his reign and then later, in the years that followed, call for others as he saw fit.

“We find royal decrees to that effect in ancient Mesopotamian cultures that predate the origin of Israel,” Bergsma says. “A year of freedom would be declared that would erase debt, reunite families, and cancel the sale of ancestral land. The Israelites didn’t have a king, though, and it wasn’t foreseen that they would have one for a while, so God was instructing them to do what a king would normally do.”

As in all things, however, God had a deeper reason for instituting the jubilee.

“At its heart was his wish that his people would never be so economically burdened that the family would be destroyed and the faith not transmitted,” explains Bergsma.

Unfortunately, as with most things God told them to do, the ancient Israelites failed to consistently celebrate the jubilee. Some half-hearted attempts to reinstitute it are mentioned in Jeremiah 34, late in the history of the Southern Kingdom of Judah, and again, after the Babylonian exile, some of the reforms of Nehemiah were inspired by it.

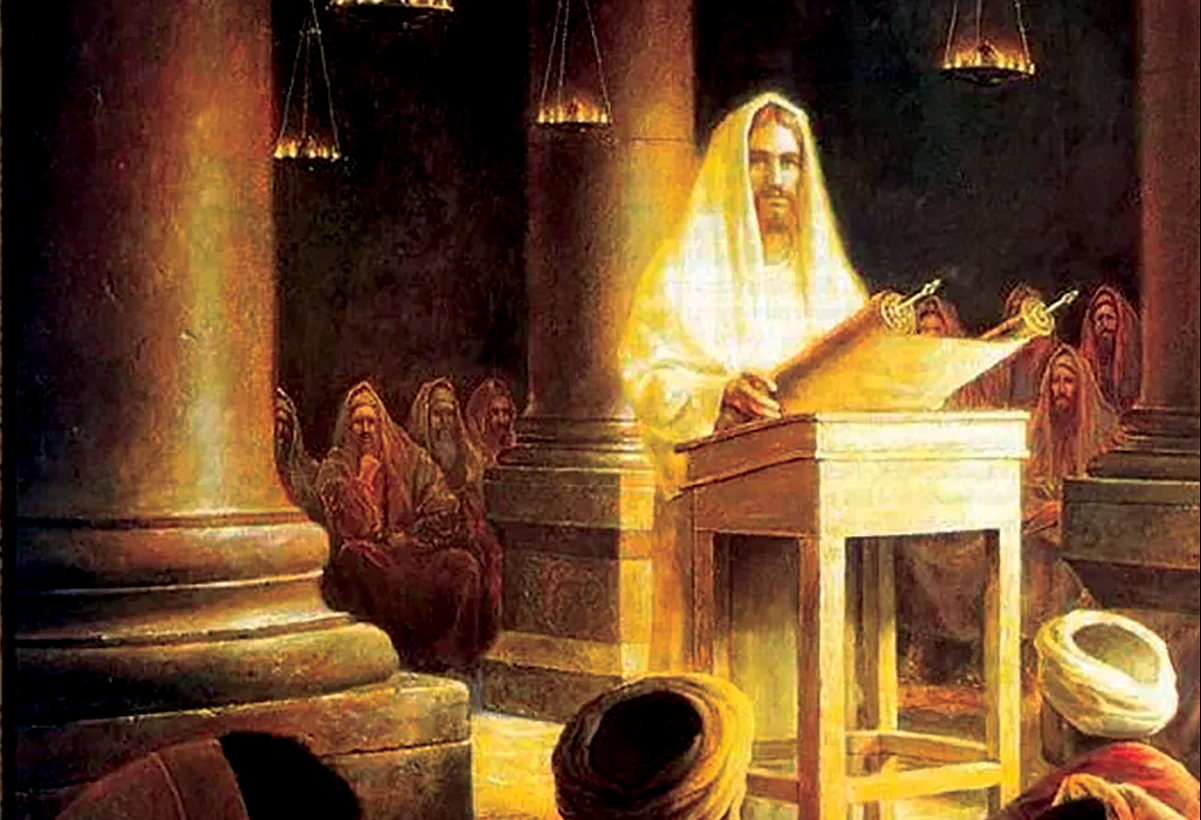

Jesus in the synagogue: “The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me.”

As the centuries passed, the Jews increasingly came to associate the idea of a jubilee with the coming Messiah. The prophet Isaiah hints at this when he declares:

“The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me to bring good tidings to the afflicted; he has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound; to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor, and the day of vengeance of our God” (Isa. 61:1-2).

In other words, explains Bergsma, “People are beginning to see the jubilee not as a legal thing, but rather as an era of liberation that the Messiah is going to inaugurate. That’s why when Jesus reads from Isaiah 61 in Luke 4, it is so exciting to the populace because they associate that prophecy with the coming of God’s anointed.”

That excitement was strengthened by a prophecy in the Book of Daniel (9:25-27), in which the Archangel Gabriel tells Daniel 70 weeks of years will pass until the Messiah comes. That translates to 490 years or 10 jubilee periods.

“Jews were aware of that chronology,” says Bergsma. “And while you can calculate it different ways from different starting points, one of the reasons for the messianic fervor during Jesus’ lifetime is because the Jews had figured out Daniel’s time stamp was near its end. The Messiah had to be coming soon.”

The expectation of a messianic jubilee is also reflected in the Dead Sea Scrolls, which talk about a messianic Melchizedek, who would proclaim a jubilee that freed people from the debt of their sin and from slavery to Satan (or Belial, the Essene word for the devil).

“What’s really cool,” says Bergsma, “is that this particular document quotes Leviticus 25 and Isaiah 61. And when we look at Luke 4, after Jesus reads from Isaiah 61, he performs an exorcism, liberating a man from Satan. Then, in the following chapter, he forgives the paralytic’s sin. He was doing the things the Essenes expected the messianic Melchizedek to do. It’s like it was intentional on Jesus’ part and Luke’s part.”

A New Jubilee

With Jesus’s death and resurrection, the hoped-for jubilee came. The debt for humanity’s sin was paid and freedom from slavery to sin was offered to all who put their faith in Jesus.

Then, less than 40 years later, Jerusalem fell, the Jewish temple was destroyed, and the Jewish people were scattered. From that point forward, there were no more attempts by the Jews to restore the practice of jubilee, with the rabbinic literature arguing that it was only necessary when Israel was settled on its ancestral land.

In the centuries that followed, however, the idea of jubilee—and particularly the significance of the number 50—lingered in the Church. In the Middle Ages, monks who had remained faithful to their vows for 50 years celebrated the anniversary of their first profession with a jubilee, while both hymns and sermons from the era associate the number 50 with the idea of remission.

Possibly around the year 1200, pilgrims were invited to travel to Rome to receive a special indulgence—the partial or complete remission of the temporal punishment resulting from sin—either for themselves or the souls in purgatory. Almost a century later, some particularly long-lived pilgrims convinced Pope Boniface VIII to do the same. At least, that’s what the treatise De Anno Jubileo claimed. Written by one Cardinal Giacomo Stefaneschi, a friend and advisor to Boniface, it laid out some of the justifications for the pope’s decision to grant special indulgences to pilgrims who traveled to Rome in 1300.

Few people, however, seemed to need the justifications. Witness accounts testify that hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of men and women from throughout Christendom made the arduous journey across land, sea, and mountain to visit Rome that year. One account, from the contemporary historian Villani, who himself made the pilgrimage, says that every day throughout the jubilee year, an additional 200,000 people were in Rome.

When Boniface declared the jubilee, his stated hope was that future pontiffs would do the same every hundred years. But 50 years later, the Church was in crisis.

Atoning for Sin

Just five years after the Jubilee of 1300, the Church’s cardinals elected a Frenchman, Clement V, to the papacy. Clement, however, had no interest in leaving his native country for the rough and unsophisticated streets of Rome. So, he didn’t. Instead, he had the entire curia come to him and take up residence in Avignon. There the popes remained for the next 76 years, at first dwelling in luxurious residences in a Dominican monastery, then building an even more luxurious palace of their own on the site of the old bishop’s residence.

Some good was accomplished by the Avignon popes, and a few of them, at least on the personal level, were, if not holy men, good men. Clement VI walked the streets of Avignon during the plague, caring for the sick and administering the sacraments to the dying. Benedict XII and Innocent VI expelled some of the more vicious elements (including prostitutes) from the papal courts, forced absentee bishops and clergy back to their dioceses and parishes, and reined in abuses among religious orders.

But, by and large, the Avignon Papacy was a disaster for the Church, with the popes doing the bidding of France’s kings and queens and with licentiousness and corruption almost everywhere. The poet Dante declared that the pope had become nothing more than the “King of France’s chaplain,” while Petrarch called Avignon “the Babylon of the Apocalypse.” The Franciscans became openly hostile to the pope and described the situation as the “Papal Babylonian Captivity.”

St. Bridget of Sweden

And that’s when St. Bridget showed up in Avignon.

A mother of eight, widow of a Swedish nobleman, and well-known mystic, Bridget was intimidated by no one, including the pope. With all the confidence of a noblewoman who has regular one-on-one chats with Jesus and his mother, Bridget informed the pope at the time, Clement VI, what she thought of the Avignon papacy. He must return to Rome, she declared, and he must atone for his sin.

Clement declined on both counts. He did, however, agree to one of Bridget’s other demands, promising her to declare 1350 another Year of Jubilee and not wait for a successor to do so in 1400 (as originally stipulated by Boniface VIII).

And so, the second official jubilee took place. The pope didn’t go. He stayed in Avignon. But hundreds of thousands of others did, some asking for forgiveness for their own sins, more begging God’s mercy on the Church and hoping their piety could bring the pope home.

And so, it has continued, down through the centuries.

Nicholas V, pope from 1447-1455, called for jubilees every 25 years.

It took another 26 years for God to answer those prayers. Thanks to the persuasive witness of St. Catherine of Siena, Gregory XI ended the Avignon Papacy in 1376. But then, within months of his death, a greater crisis struck the Church: the Great Western Schism.

It was Gregory’s successor, Urban VI, who called for the next jubilee year in 1390, hoping the prayers of the faithful might convince the anti-pope, Clement VII, to give up his claim to the papacy. Urban also declared that a jubilee should take place every 33 years, fixing the length between jubilees as the same number of years as Christ’s earthly life.

Ten years later, however, in 1400, the schism was still in full swing when so many pilgrims showed up in Rome, expecting a plenary indulgence, that Pope Boniface IX granted them one, despite not having scheduled a jubilee. Then, in 1423, another jubilee took place according to the schedule set by Urban. Once Pope Nicholas V ascended to the Chair of Peter in 1447, however, he decided to wait until 1450 to celebrate the next jubilee. After that, it was officially decided that the Church would call for a jubilee every 25 years.

Promise and Hope

Over the past 571 years, the Church’s jubilee years have been marked by tragedy. Two hundred people were trampled to death on the bridge of the Castel Sant’Angelo one year. Another year, the famous opening of the sealed holy doors to one of Rome’s major basilicas resulted in mounds of concrete falling on innocent bystanders.

Other jubilees, like that of 1475, were the occasion for beginning work on some of the Church’s greatest architectural treasures, including the Sistine Chapel.

Some jubilees were skipped altogether. In 1800, the Church’s standoff with Napoleon made a jubilee impossible. In 1850, difficulties with the new Italian Republic sent Pope Pius IX into exile and no jubilee took place. In 1875, Pius did call for a jubilee, but he remained trapped within the Vatican unable to participate in ceremonies throughout the city due to Rome’s occupation by the troops of King Victor Emmanuel II.

Every jubilee of the 20th century was celebrated with pomp and circumstance, all leading up to the Great Jubilee of 2000, when St. John Paul II welcomed more than 10 million pilgrims to Rome. Hundreds of millions more celebrated that jubilee in their home dioceses, where special holy doors were set up in cathedrals and parishes, with indulgences granted to the faithful who walked through them, prayed, confessed, and received Communion.

And now, we are a little more than three years away from the next ordinary jubilee in 2025.

Like all the jubilees that have come before it, this next jubilee will be marked by joy—literally by jubilation—for the Messiah has come. The promise of deliverance has been fulfilled. All washed by the waters of baptism are no longer slaves but rather adopted sons and daughters of God.

Also, like the jubilees that have come before it, this next one will be filled with hope—for the Messiah to come again, for deliverance from the sorrows of this life, for everything, in heaven and earth, to be made new.

And, like all other jubilees, grace will flow. There will a superabundance of mercy—a superabundance of God’s life—poured out on all who ask for it, freeing us and the holy souls in purgatory from the temporal punishment due to us for our sins.

That is the jubilee promise. It is the year of the Lord’s favor, a symbol in time of the work the Lord has been doing every day for the last 2,000 years.