Rise and Fall

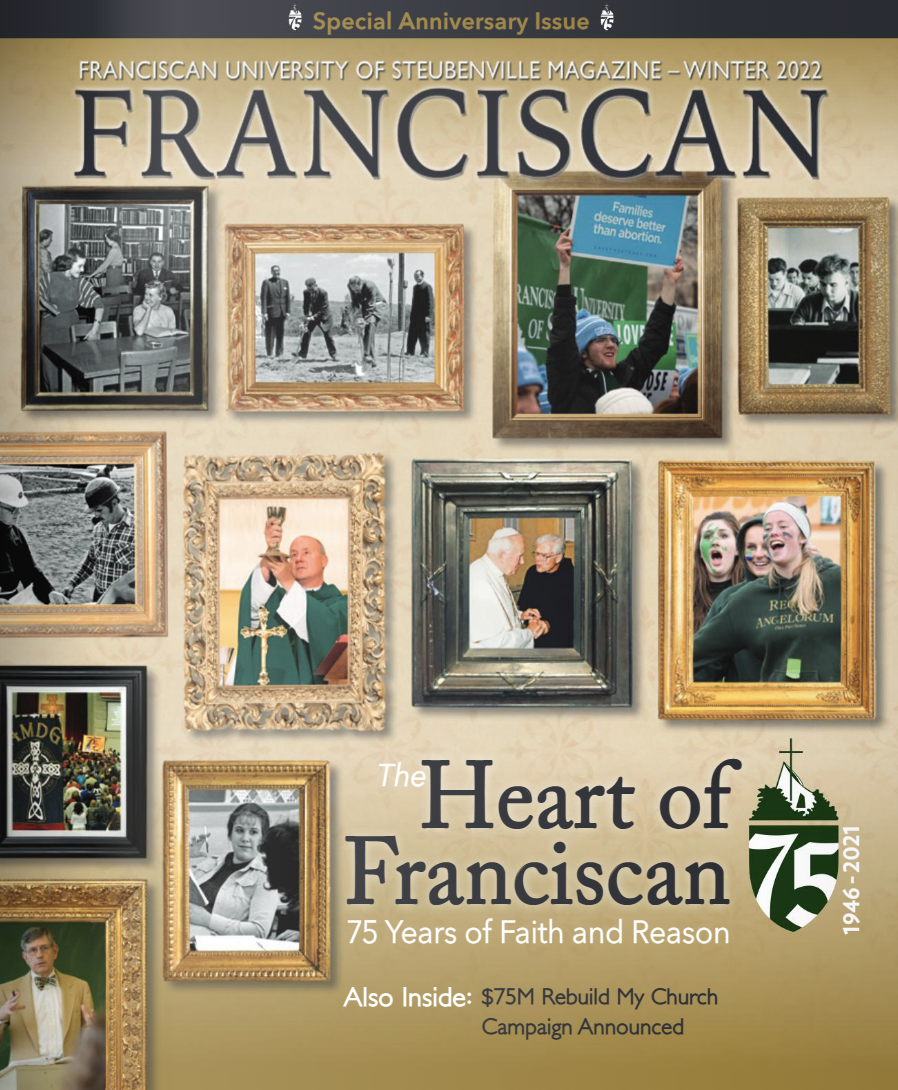

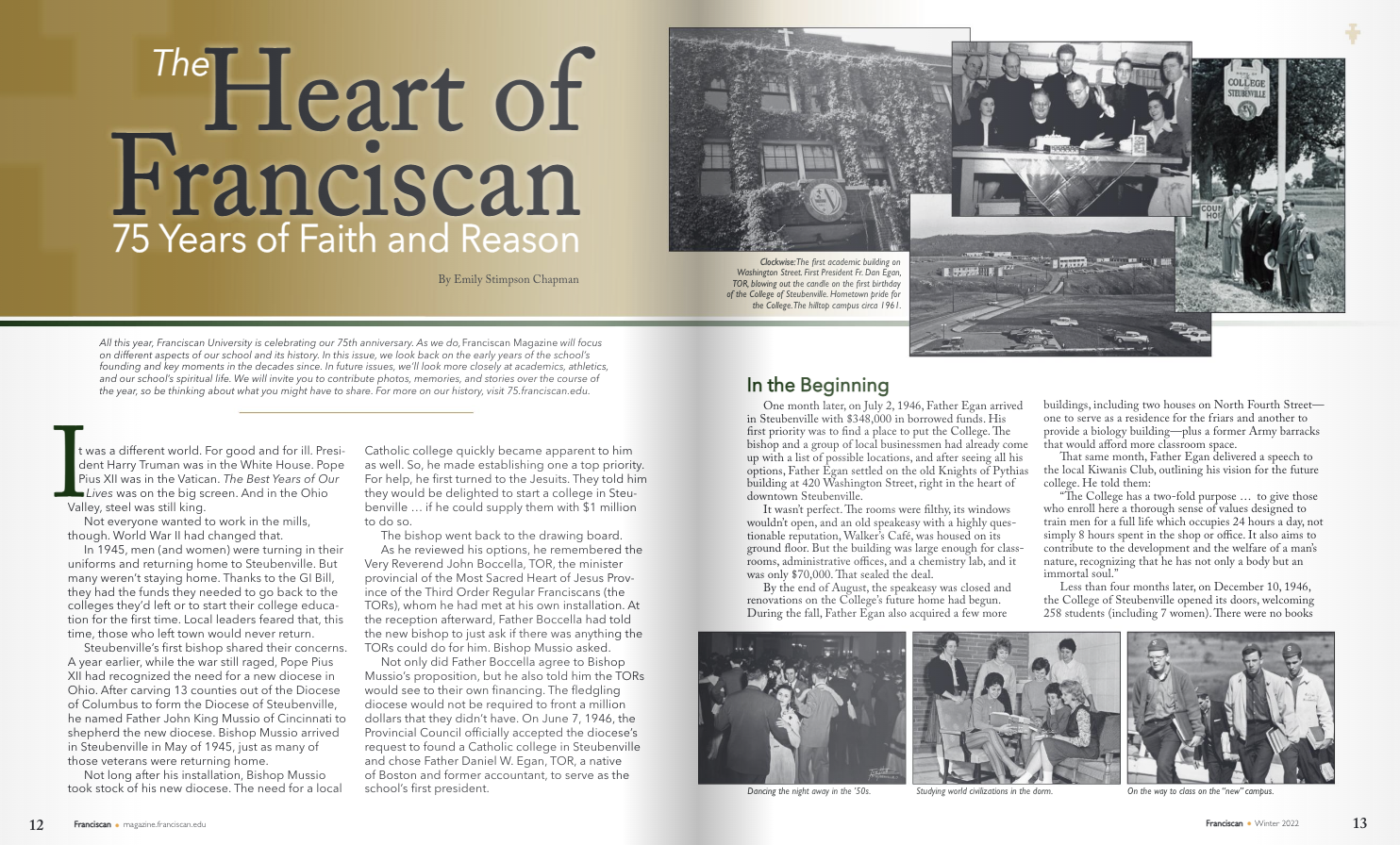

The next decade saw an explosion of success and growth for the College of Steubenville. The student body grew, the basketball team—under the leadership of Coach Hank Kuzma—had one victory after another, and in 1954, with the help of local businessman Michael Starvaggi, Father Egan purchased 40 acres of land overlooking the Ohio River. The land, which was just one mile from downtown, was to be the school’s new campus.

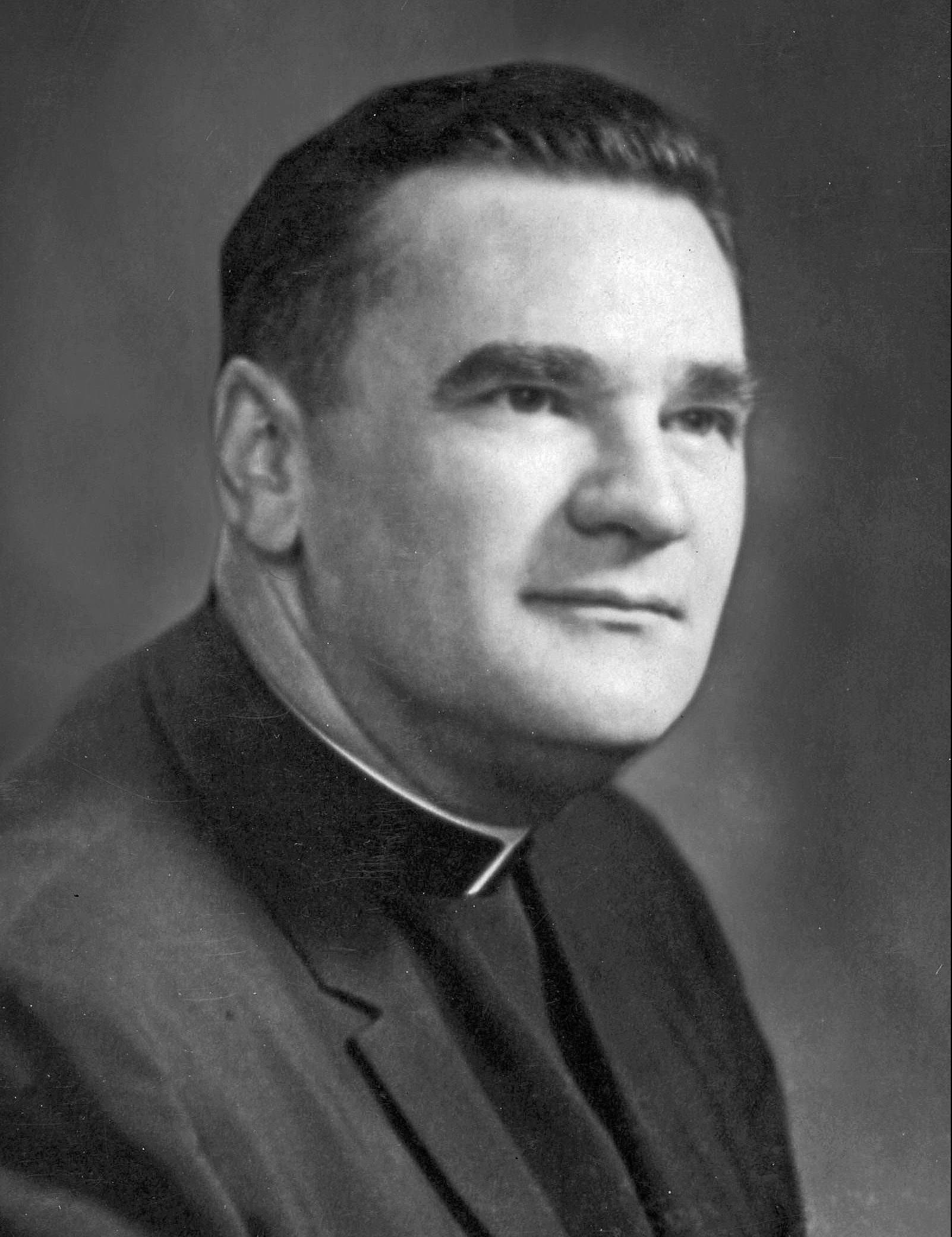

Father Egan never lived to see that campus. In 1959, not long before construction began, a fire broke out in the downtown TOR friary. Father Egan died due to smoke inhalation. After the school, city, and TOR community mourned his passing, his successor was chosen: Father Kevin Keelan, TOR.

For three years, Father Keelan led the school, overseeing the construction of six new buildings on the 40 acres Father Egan had purchased and supervising the school’s move from downtown to its new hillside campus in 1961. By that point, the student body had grown to 250 resident students and 600 commuter students.

In 1962, Father Keelan became minister provincial for the TORs. He was succeeded by Father Columba Devlin, TOR, who governed the College through seven years of tremendous growth. Father Keelan then returned to serve as president during what would be the College’s most tumultuous years, 1969 to 1974.

When Father Kevin was reelected to the presidency, enrollment at the College of Steubenville was at an all time high of 1,111 students, and the surplus of students was matched by a surplus of money. For the first time in the College of Steubenville’s history, it was debt free.

The field that became Franciscan University of Steubenville.

Quickly, however, that changed. Other local colleges were built in the late 1960s, and the draft, which had kept so many young men in college, ended. The cultural upheaval of the late 1960s and early 1970s, with its rejection of the Church, authority figures, and traditional sexual mores, also made recruitment to a traditional Catholic college difficult. The combination of all three changes led enrollment to plummet. In just two years, the school lost 20 percent of its student body.

Father Kevin first responded to the declining enrollment by laying off faculty and cutting back on program funding. Then, hoping to attract more students, he had the curriculum revised. All philosophy requirements were abandoned, and the theology requirements gutted.

From there, it got worse.

In 1973, only six students and eight members of the faculty attended the first Mass of the school year. A year later, two dormitories stood empty, banks refused to lend the school money, and one educational journal warned investors and potential students against the College, listing it as one of 13 colleges likely to close by year’s end. Faculty started handing in their resignations, leaving for more secure positions at other schools, and a “For Sale” sign went up outside St. Thomas More Hall.

Father Keelan was a good and faithful priest, but he knew he wasn’t the man to save the College of Steubenville. He didn’t know if that was even possible. But if it was, someone else needed to do it. In 1974, he submitted his resignation to the Board of Trustees, and the search for a new president began.

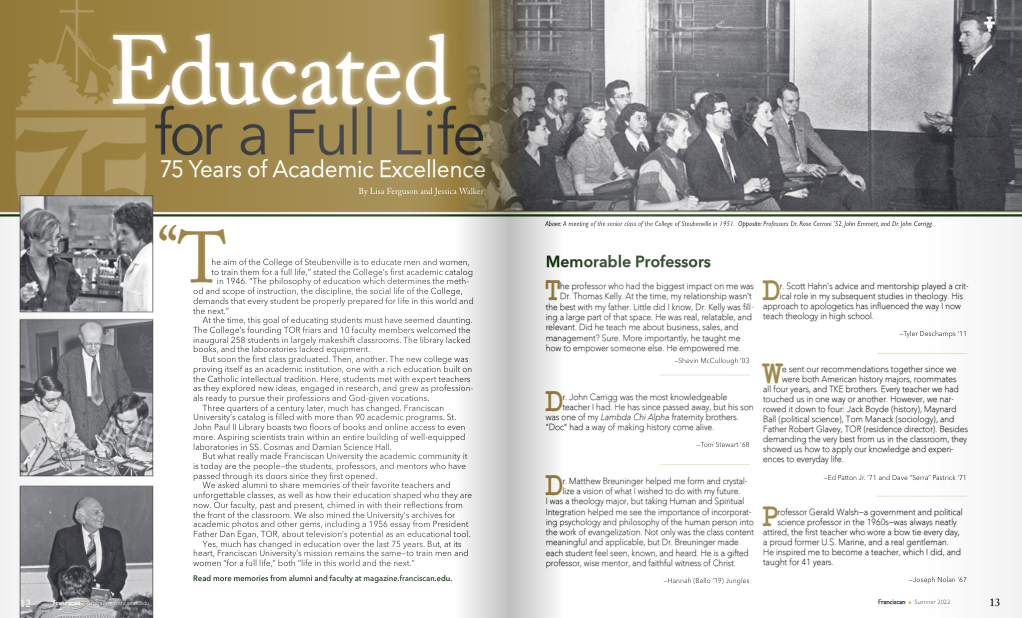

Fr. Dan Egan, TOR, reviews plans for the new campus.

A New Beginning

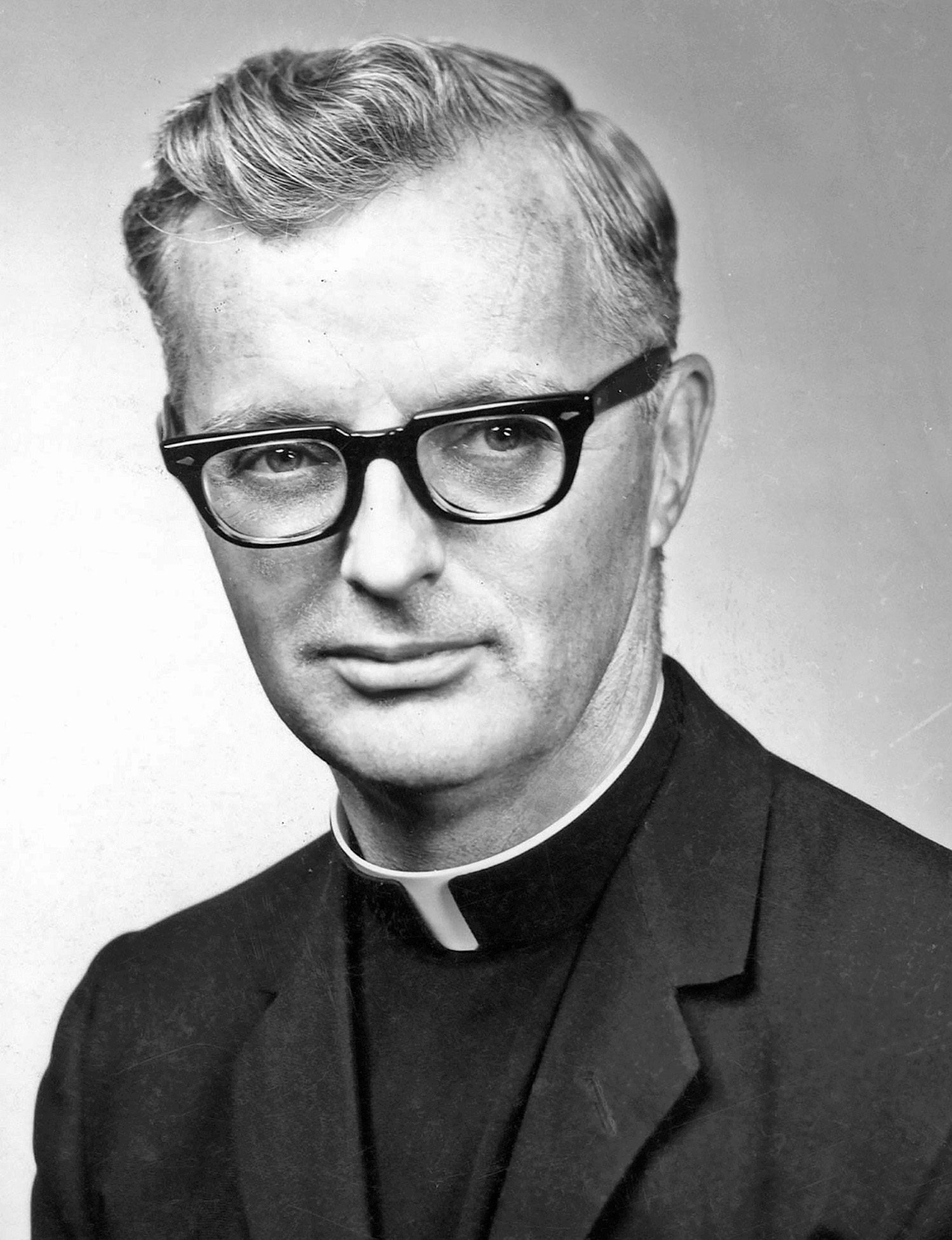

All these years later, nobody knows exactly how many people applied to be president of the College of Steubenville in 1974. It was hardly a choice position. But the board did find four men at least willing to be interviewed for the job. Three of those men went before the hiring committee and outlined their plans for closing the school. The fourth man, the College’s former academic dean, Father Michael Scanlan, TOR, outlined his plan for saving the school. They hired him.

The plan Father Scanlan laid out during his interview was simple.

The College, he argued, could be saved. Not by following the path of other Catholic schools and watering down the faith. But by becoming more deeply Catholic and making “Jesus Christ the Lord of the campus in every respect.”

The trustees took a gamble on that plan, and on October 5, 1974, Father Scanlan became the school’s fourth president. The first thing he did was to march over to St. Thomas More Hall and rip down the “For Sale” sign.

“Even if you’re going to die, you don’t advertise it,” he announced.

“Jesus Christ the Lord of the campus in every respect.”

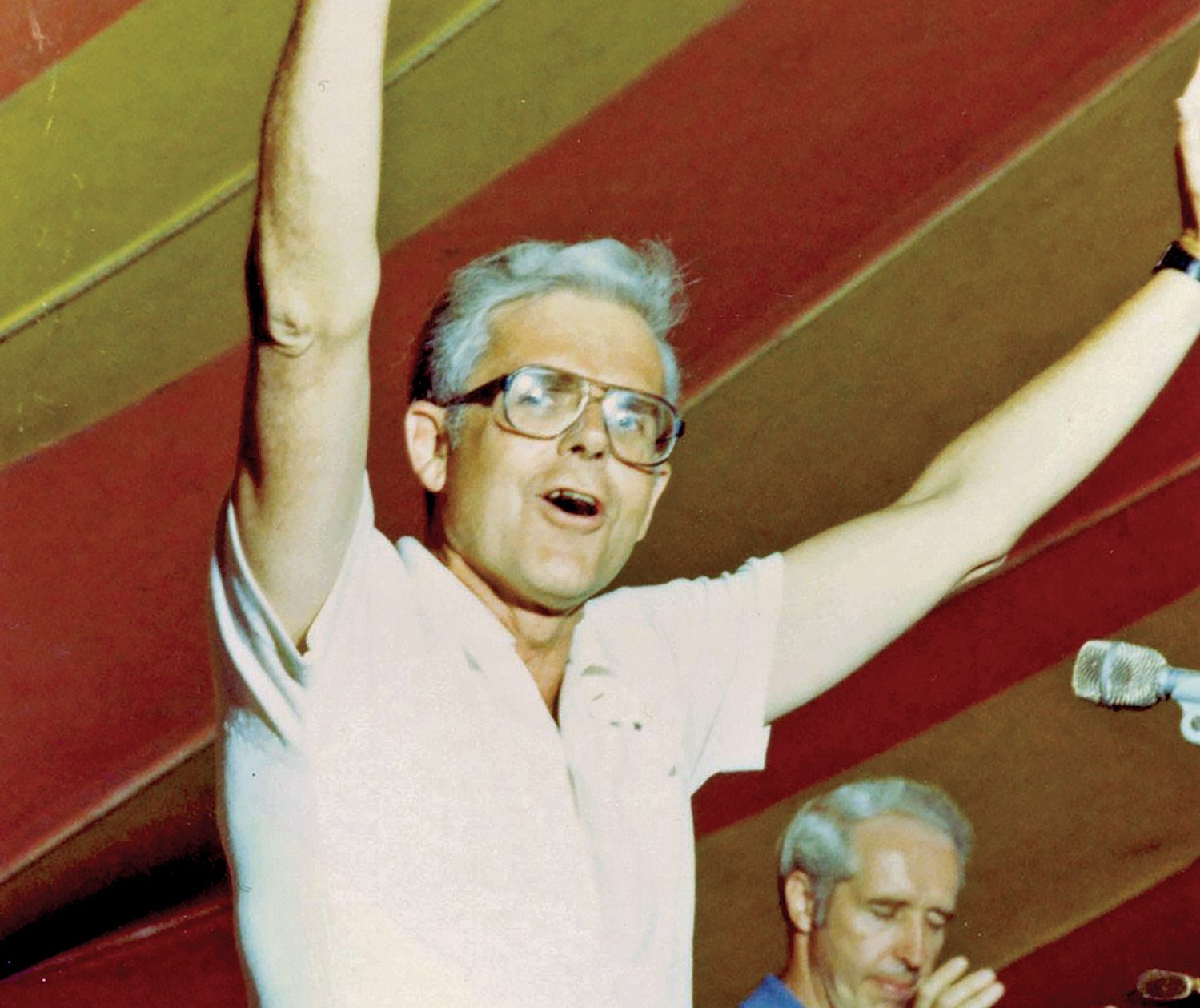

Fr. Michael Scanlan, TOR, and Fr. Francis Martin at a Priests Conference in the late 1970s.

But the school didn’t die. As soon as he accepted the position of president, Father Michael began inviting friends from the Catholic charismatic renewal movement to join him in Steubenville and partner with him in the school’s spiritual rebirth. Then, at the beginning of the fall semester, instead of switching the school’s Sunday Liturgy to Saturday evening, as many students had requested, Father Scanlan began offering every Sunday Mass himself. He also told students to expect it to be at least 90 minutes long. There would be more preaching, more singing, and more prayer, not less.

Father Michael also immersed himself in the life of the students, on and off campus. He went to their athletic games, to their parties, and to their late-night study sessions in the residence halls. The more time he spent with the students, the more he realized that changes even more drastic than 90-minute liturgies needed to be made.

So, in December 1974, he called a meeting. Standing before the entire College, Father Scanlan explained that too many students were falling through the cracks. They were hurting, lonely, and needed to relearn the basics of Christian friendship. They needed community. And he wanted to give it to them.

To make that possible, Father Scanlan announced that every student on campus would be required to join what he called a “household”—a fraternal community designed to foster intimate friendships and provide students with the emotional support he believed they desperately needed.

“As I mingled with the students that [first] fall it became obvious to me that renewal at the College had to begin with changing [students’] sad and lonely lives,” he later explained.

At first, reactions were mixed. Some wholly embraced the concept. Others reluctantly went along with it. And more than a few rebelled, arguing that the president had no right to mandate any such thing. But Father Scanlan held firm. He believed nothing could change the campus culture more powerfully than Christian friendship. And he believed nothing could foster Christian friendship more fully than households.

He was right.

First Youth Conference, 1976.

For the first five years, until 1980, participation in a household was mandatory. Students who didn’t feel comfortable in a household centered on the Catholic faith were allowed to form non-faith-based households, including an athletic household and Greek households, which offered students support, but without specific spirituality. After 1980, however, households had become such an integral part of campus life that the requirement to belong to one was lifted.

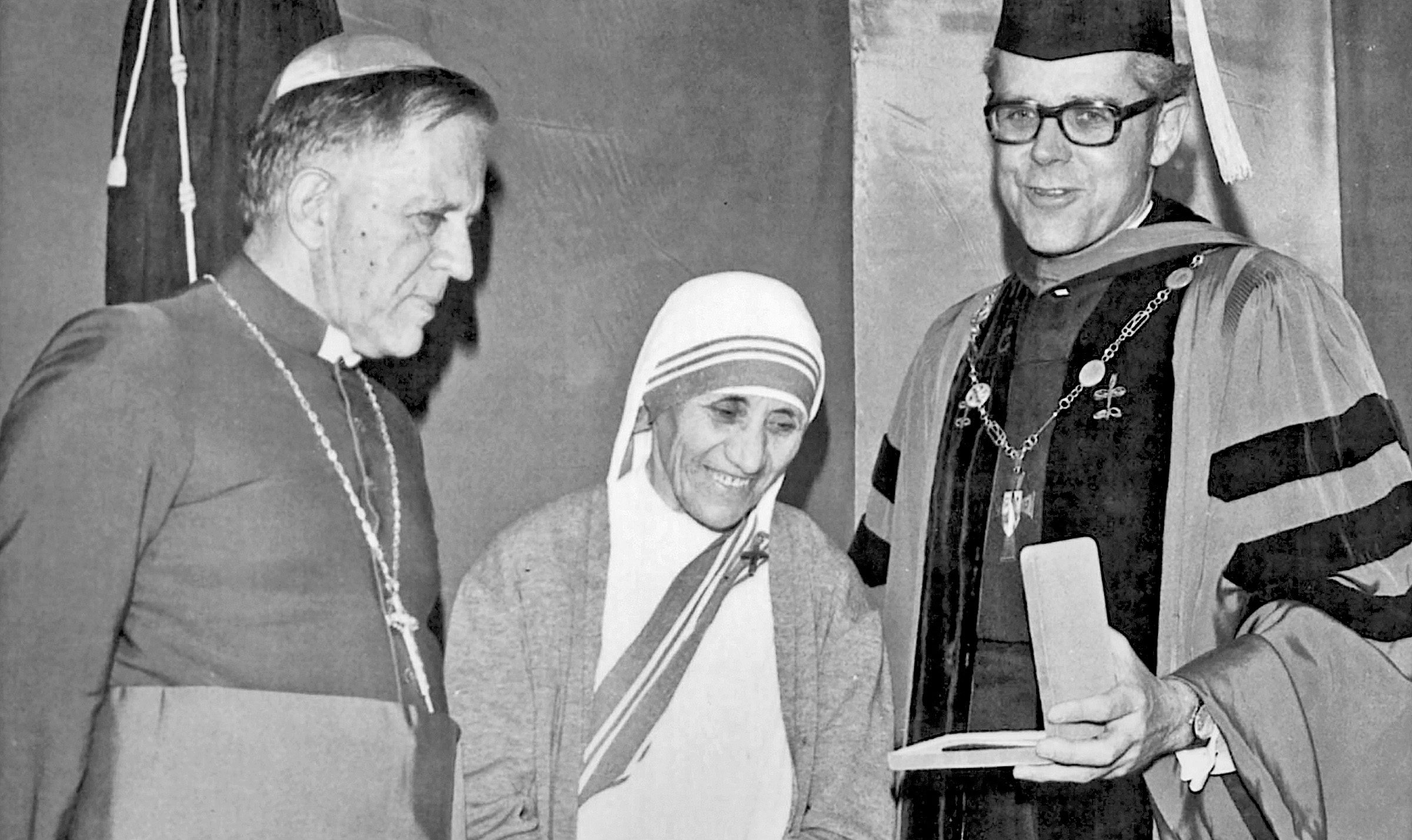

All the while, there was pushback from students who took issue with the direction in which Father Michael was taking the College, as well as from a group of faculty who introduced a resolution of no confidence in the president. The resolution was defeated, Father Scanlan stayed the course, and slowly but surely, the College grew. New students enrolled. New faculty were hired. New majors and graduate programs began. And in 1976, the College was certain enough of its future to invite Mother Teresa of Calcutta to campus to deliver the commencement address and receive its highest non-academic honor, the Poverello Medal.

To Father Scanlan’s delight, she accepted the invitation. Before the founder of the Missionaries of Charity arrived on campus, however, few among the faculty and staff had any idea who she was. It would be three more years before the Nobel Peace Prize Committee would choose the missionary sister to receive one of the world’s highest honors and make her a household name. When asked who their commencement speaker was going to be, most Steubenville students replied, “Some nun friend of Father Mike’s.” But, after hearing her speak, they never forgot her or her message.

“She challenged us,” remembered Theresa (Rocco ’78) DiPiero, who served as an aide to Mother Teresa for part of that day. “She said she dealt day to day with physical poverty, but our poverty was so much worse, because ours is a poverty of love. We ignore each other, we don’t reach out, we don’t know our neighbors. We are people walking around so poor of spirit. It was a very challenging word to the graduates.”

Mother Teresa receives the 1976 Poverello Medal from Fr. Scanlan.

Growth in Faith

Forty-six years have passed since Mother Teresa stood on stage with Father Scanlan, speaking those words. Three more presidents have come. Two—Father Terence Henry, TOR, and Father Sean O. Sheridan, TOR—have left. The third, the current president Father Dave Pivonka, TOR ’89, is the school’s first alumnus to lead his alma mater.

When Father Pivonka first came to campus as a student in 1986, the College of Steubenville had been a University for six years, earning the change in status after the launch of its Master of Theology Program in 1980. It also had been known as Franciscan University of Steubenville for less than one year, with the Board of Trustees deciding to change the name in 1985 to reflect the school’s Franciscan heritage and wider Catholic mission.

Likewise, in 1986, the University’s Summer Conferences, which now welcome thousands of people to campus every year (and reach 50,000 teens in conferences across North America) had been going strong for 11 years. The Pre-Theologate Program, which would go on to prepare nearly 300 young men for the priesthood and religious life, had just been established. Within three years, by 1989, the full-time undergraduate student enrollment would reach 1,179, surpassing at last the previous high set in 1970. Also in 1989, for the first time, all the TOR friars and theology faculty would take the Oath of Fidelity to the Church’s magisterium. Franciscan was the first university in the country to do so publicly.

In many ways, the Franciscan University of Steubenville Father Dave knew as a student was well on its way to becoming the University he would someday lead as president. It was no longer a scrappy start-up or a financially imperiled college attended almost exclusively by Ohio Valley residents. It was a nationally recognized university that drew students from all 50 states. But even then, it was hard to imagine the further growth that would take place over the next 30 years, before Father Dave would return to lead as president.

2017 Vocations Fair.

“Franciscan University is one of the brightest lights in the Catholic Church today. I travel quite extensively, and I honestly don’t know of another university that understands the importance of ‘dynamic orthodoxy’ as Franciscan does. Orthodoxy is essential but not enough. The power of the Holy Spirit is essential for providing the dynamism that needs to animate our lives and work. Franciscan has sent forth its graduates throughout the United States and to many international destinations as well. Everywhere they go they are a light.”

– Dr. Ralph Martin, former Franciscan University trustee and current director of Graduate Theology Programs in the New Evangelization at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit

In 1991, Franciscan University joined forces with Austrian architect Walter Hildebrand in the restoration of the Kartause Maria Thronus Iesu, a centuries-old Carthusian monastery enfolded in the foothills of the Austrian Alps. The plan was to give Franciscan University a permanent base in Europe, a place where students could live, learn, and immerse themselves in the once great Catholic culture of Europe and deepen their understanding of the relationship between Church and culture.

As the second Austrian Program Director Richard Fougerousse explained about the program’s goals, “Christopher Dawson once wrote that history is the cure for parochialism in time. I think the same thing applies to geography and culture. Going abroad and actually learning something about another culture is the great palliative for parochialism culturally.”

Today, more than 400 students annually call the old monastery home, and nearly 70 percent of Franciscan students spend a semester there during their time at Franciscan.

2005 study abroad community in Gaming, Austria.

The early 1990s also saw the founding and growth of Franciscan University’s Catechetics Program. Under the leadership of Professor Barbara Morgan, the program grew from a concentration within the Theology Program to its own major and master’s track. Attracted by the orthodoxy and depth of the school’s Theology Program (which already enrolled more students than any other Catholic university in the country) and the proven expertise of Morgan, bright, faithful, and charismatic young people began flocking to the University. In the years that followed, Franciscan’s theology and catechetics faculty helped form some of the Church’s most effective evangelists and teachers in recent decades, including Jeff Cavins, Curtis Martin, Dr. Ted Sri, Dr. Mary Healy, Jason Evert, and many more.

Through it all, Franciscan’s reputation grew and spread. Bishops and pastors sought out Franciscan’s graduates to staff their chanceries and parishes, while parents dreamed of sending their children to Franciscan, where they knew they would receive an authentically Catholic education. Even the future saint, Pope John Paul II developed a love for the school. “Ahhhhhhh, Steubenville,” he would say with a smile whenever someone from Franciscan crossed his path.

With the beginning of a new millennium, Franciscan expanded its reach even further. Under the leadership of Father Terence Henry, TOR, Franciscan more than doubled its campus square footage with the purchases of the former Belleview Golf Course, Assisi Heights, and the green strip alongside University Boulevard, increasing the campus size to 244 acres. In 2011, it also emerged as one of America’s leaders in the fight for religious liberty. When the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services mandated Catholic institutions to pay for drugs and procedures that violate core Church teachings, Franciscan filed suit against the federal government contesting the mandate and helped lead the charge against it in both academic circles and the popular press.

As Franciscan’s national reputation grew, so did its reputation for academic excellence. Beginning in 2007 when Father Terry was president and continuing through the presidency of Father Sean, the University established a host of academic centers and institutes, including the Center for Bioethics, the Center for Leadership, the Catechetical Institute, the Franciscan Institute for Science and Health, the Franciscan Institute for World Health, and the Veritas Center for Ethics in Public Life.

That work of the University’s faculty and students was recognized by U.S. News & World Report, as well as the Newman Guide to Choosing a Catholic College, First Things Magazine, Forbes Magazine, Kiplinger Personal Finance Magazine, the Templeton Honor Roll, and the Young America’s Foundation, all of which began regularly including Franciscan University on their lists of America’s best colleges.

As Father Sean’s presidency drew to a close, the legacy of Franciscan University seemed as sure as the legacy of those old Carthusian monks who once inhabited the Kartause. This prompted Franciscan’s sixth president to express his hope that as it is at the Kartause, “Seven hundred years from now, the minister provincial will mention the stones and paths of Franciscan University of Steubenville, noting where generations of the Franciscan University family walked and prayed and were truly transformed by Christ.”

Then, in March 2020, during the first year of Father Dave Pivonka’s presidency, the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Fall 2020 opening Mass celebrated by Fr. Pivonka outdoors due to COVID restrictions.

Stepping in Faith

In the wake of the national shutdown that followed the start of the pandemic, many small colleges across the country faced the same crisis Franciscan had been in 46 years earlier. Some closed their doors. Others withdrew offers of scholarship assistance to new and returning students. A combination of prayer, trust, and years of careful financial stewardship, however, enabled Franciscan University to respond differently.

Instead of withdrawing financial assistance from students during the fall 2020 semester, Franciscan offered free tuition to all new incoming students and increased financial aid to returning students. The Step in Faith Initiative attracted national attention. But more importantly, it ensured that the students God wanted at Franciscan University could come to Franciscan University, even in the midst of global uncertainty and increasing financial difficulties.

Step in Faith also was a statement to students, parents, alumni, and the culture at large that Franciscan University was still guided by the same spirit that enabled the TORs to say yes to Bishop Mussio’s invitation to found a school in a small town in southeastern Ohio, even when no one knew how they would pay for it.

“For Franciscan University, the Step in Faith Initiative was not merely a program,” explained Father Dave. “It’s the way we, as a community, run the University. This is the way we are going to live, no matter what the world throws at us. We are a community of faith that is going to operate according to faith. It’s the best place to be. We’re Peter walking on water. And we can’t expect the students to do something we’re not going to do. We have to model what we are asking other people to do.”

Washington, D.C., March for Life, 2020.

Seventy-five years ago, Father Dan Egan could not imagine what he was helping to found. He had no idea that his little school, which started out with fewer than 300 students from around the Ohio Valley, would grow into a major Catholic university with more than 3,000 students on campus and online and 375 faculty and staff. He didn’t know that future saints would visit the school, although he certainly hoped they would be formed at the school. He didn’t know popes would love the College, although he prayed the College would always love the pope. Household life, conferences, study abroad programs, pro-life work, research institutes—none of that entered Father Egan’s mind.

And yet, the heart of Franciscan University he did imagine. What makes Franciscan University great, what it strives to give its students, what it works to offer alumni—all that he did see. All that, he helped weave into the very fabric of the University. And his words, spoken at the very first commencement in 1950, still ring true.

“Our work in the college does not end with your commencement, but it commences then. We want to be working with you all your life. The institution will go on when all of us have passed away. It will be serving your children and their children. It may be better, it may be bigger, but it cannot want to do any more. Perhaps sometimes in these years we didn’t always do the right thing at the right time. We may have made blunders. You made them, too.

“We think in the end, though, in total results, we tried to give all your learning to you in a package that you carry away as a person. We think and we hope that will stay with you every day of your life. That you have absorbed a philosophy of life that is dominated by a true conception of culture. That you see in every man and woman the image of God, the immortal soul that Christ redeemed. And consequently, that in all your relations with your fellow man you can truly say you love your neighbor as yourself, for the love of God because God loves them.”

That remains Franciscan University’s hope. That remains Franciscan University’s goal. We may get bigger. We may get better. But we cannot hope to do any more.

Commencement, 2021.

“There is no institution in the United States that has contributed more energy and personnel to the new evangelization than Steubenville’s Franciscan University. Everywhere we look, Franciscan University graduates are involved in making the Gospel of Jesus a living reality in our time. What a blessing for the Church.”

– Archbishop Emeritus Charles Chaput, OFM Cap.