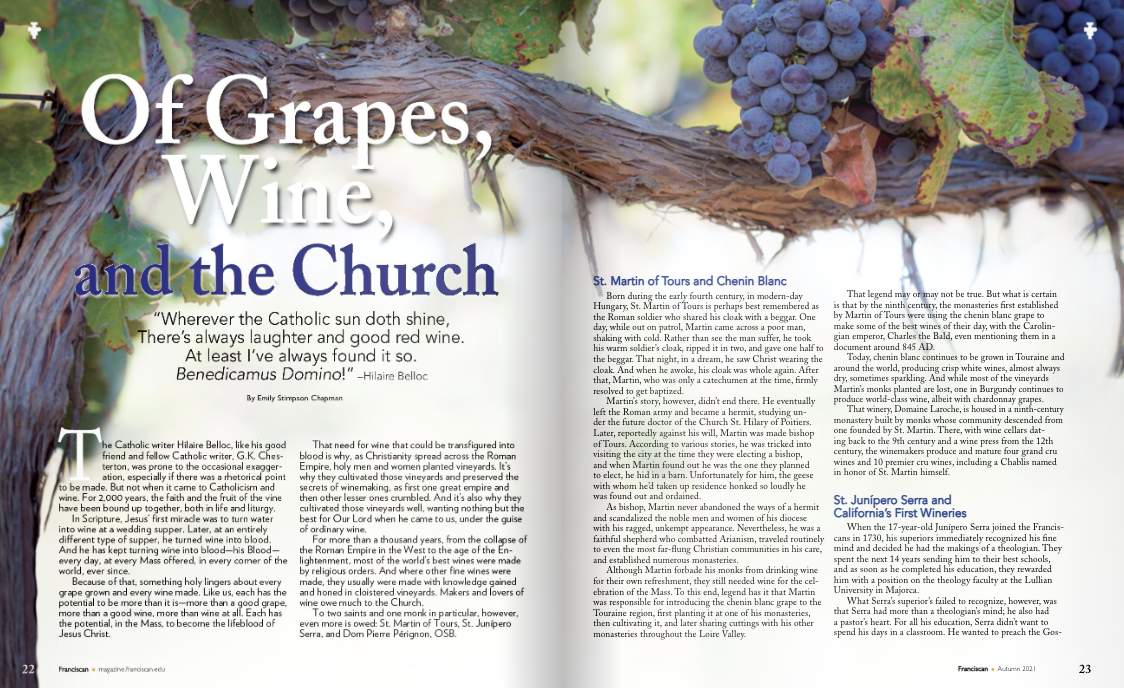

The Catholic writer Hilaire Belloc, like his good friend and fellow Catholic writer, G.K. Chesterton, was prone to the occasional exaggeration, especially if there was a rhetorical point to be made. But not when it came to Catholicism and wine. For 2,000 years, the faith and the fruit of the vine have been bound up together, both in life and liturgy.

In Scripture, Jesus’ first miracle was to turn water into wine at a wedding supper. Later, at an entirely different type of supper, he turned wine into blood. And he has kept turning wine into blood—his Blood— every day, at every Mass offered, in every corner of the world, ever since.

Because of that, something holy lingers about every grape grown and every wine made. Like us, each has the potential to be more than it is—more than a good grape, more than a good wine, more than wine at all. Each has the potential, in the Mass, to become the lifeblood of Jesus Christ.

That need for wine that could be transfigured into blood is why, as Christianity spread across the Roman Empire, holy men and women planted vineyards. It’s why they cultivated those vineyards and preserved the secrets of winemaking, as first one great empire and then other lesser ones crumbled. And it’s also why they cultivated those vineyards well, wanting nothing but the best for Our Lord when he came to us, under the guise of ordinary wine.

For more than a thousand years, from the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West to the age of the Enlightenment, most of the world’s best wines were made by religious orders. And where other fine wines were made, they usually were made with knowledge gained and honed in cloistered vineyards. Makers and lovers of wine owe much to the Church.

To two saints and one monk in particular, however, even more is owed: St. Martin of Tours, St. Junípero Serra, and Dom Pierre Pérignon, OSB.

St. Martin of Tours and Chenin Blanc

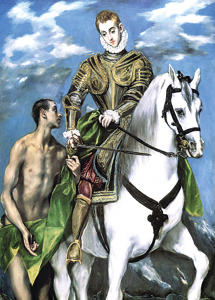

St. Martin of Tours, known for his generosity and possibly the chenin blanc grape.

Born during the early fourth century, in modern-day Hungary, St. Martin of Tours is perhaps best remembered as the Roman soldier who shared his cloak with a beggar. One day, while out on patrol, Martin came across a poor man, shaking with cold. Rather than see the man suffer, he took his warm soldier’s cloak, ripped it in two, and gave one half to the beggar. That night, in a dream, he saw Christ wearing the cloak. And when he awoke, his cloak was whole again. After that, Martin, who was only a catechumen at the time, firmly resolved to get baptized.

Martin’s story, however, didn’t end there. He eventually left the Roman army and became a hermit, studying under the future doctor of the Church St. Hilary of Poitiers. Later, reportedly against his will, Martin was made bishop of Tours. According to various stories, he was tricked into visiting the city at the time they were electing a bishop, and when Martin found out he was the one they planned to elect, he hid in a barn. Unfortunately for him, the geese with whom he’d taken up residence honked so loudly he was found out and ordained.

As bishop, Martin never abandoned the ways of a hermit and scandalized the noble men and women of his diocese with his ragged, unkempt appearance. Nevertheless, he was a faithful shepherd who combatted Arianism, traveled routinely to even the most far-flung Christian communities in his care, and established numerous monasteries.

Although Martin forbade his monks from drinking wine for their own refreshment, they still needed wine for the celebration of the Mass. To this end, legend has it that Martin was responsible for introducing the chenin blanc grape to the Touraine region, first planting it at one of his monasteries, then cultivating it, and later sharing cuttings with his other monasteries throughout the Loire Valley.

That legend may or may not be true. But what is certain is that by the ninth century, the monasteries first established by Martin of Tours were using the chenin blanc grape to make some of the best wines of their day, with the Carolingian emperor, Charles the Bald, even mentioning them in a document around 845 AD.

Today, chenin blanc continues to be grown in Touraine and around the world, producing crisp white wines, almost always dry, sometimes sparkling. And while most of the vineyards Martin’s monks planted are lost, one in Burgundy continues to produce world-class wine, albeit with chardonnay grapes.

That winery, Domaine Laroche, is housed in a ninth-century monastery built by monks whose community descended from one founded by St. Martin. There, with wine cellars dating back to the 9th century and a wine press from the 12th century, the winemakers produce and mature four grand cru wines and 10 premier cru wines, including a Chablis named in honor of St. Martin himself.

“Something holy lingers about every grape grown and every wine made.”

St. Junípero Serra and California’s First Wineries

When the 17-year-old Junípero Serra joined the Franciscans in 1730, his superiors immediately recognized his fine mind and decided he had the makings of a theologian. They spent the next 14 years sending him to their best schools, and as soon as he completed his education, they rewarded him with a position on the theology faculty at the Lullian University in Majorca.

What Serra’s superior’s failed to recognize, however, was that Serra had more than a theologian’s mind; he also had a pastor’s heart. For all his education, Serra didn’t want to spend his days in a classroom. He wanted to preach the Gospel. He wanted to evangelize. He wanted to help people know who Jesus was and who they were.

After five years in Majorca, Serra got what he wanted. It took some persuading, but he finally convinced his superiors to send him to the Americas. He sailed for Mexico in 1749 and spent the next 19 years working in and around Mexico City as both a preacher and administrator. Serra loved his work and the people he served, but he still dreamed of more. He didn’t just want to preach the Gospel to the already converted. He wanted to introduce the unbaptized to Christ.

Accordingly, in 1768, when the Jesuits were kicked out of Alta California, he jumped at the chance to go north and establish missions there. At 55, with asthma and open ulcers in his legs, Serra founded his first mission in San Diego. Over the next 15 years, he established eight more missions, laying the groundwork for California’s great cities up and down the Pacific coast.

He also laid the groundwork for California’s magnificent wine industry, planting the future state’s first vineyards and building its first wineries. The grapes he planted are known as the mission grape, a varietal that had first been cultivated near Mexico City by the Franciscan missionaries who served there.

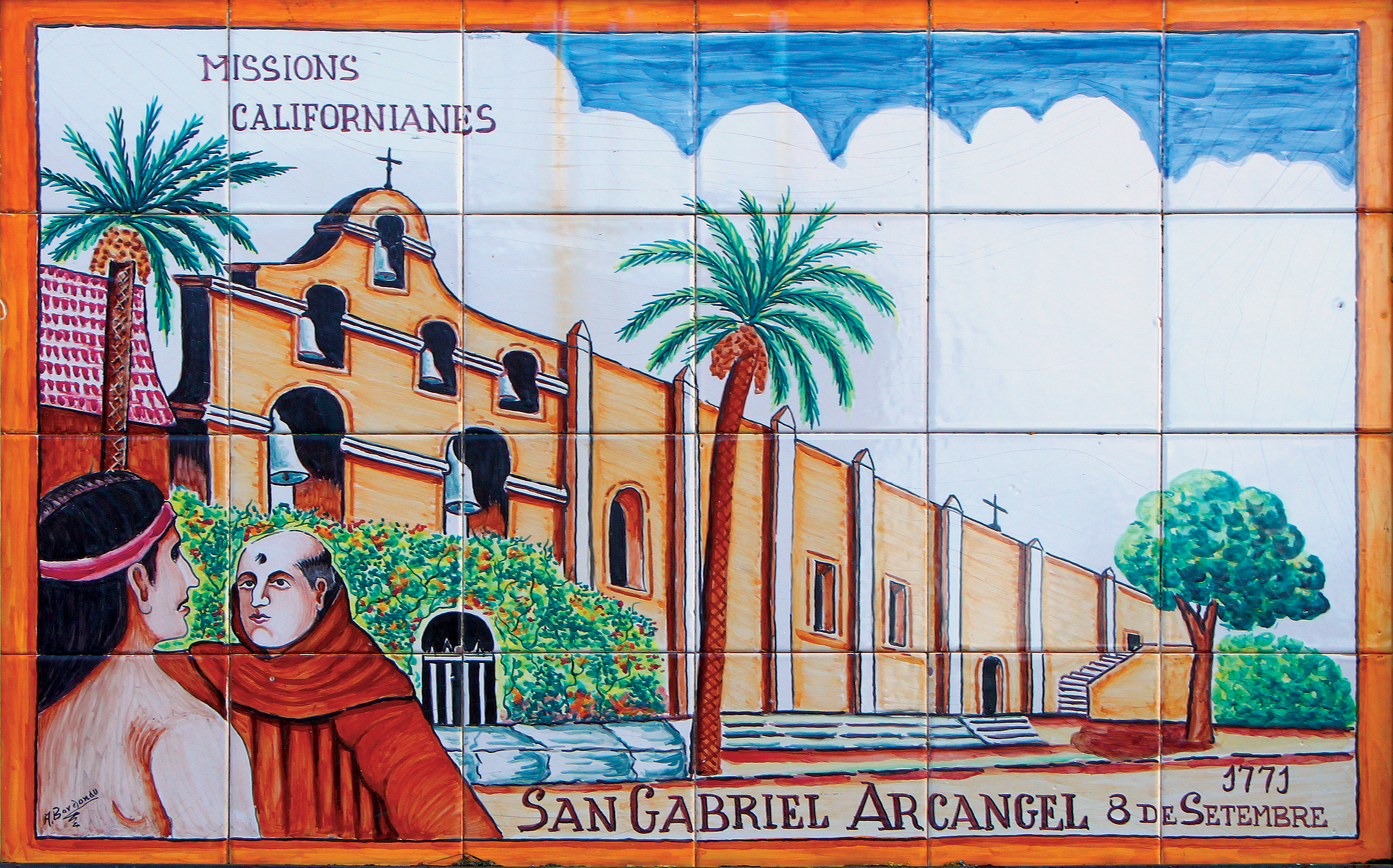

St. Junipero Serra at Mission San Gabriel, where he planted the mission grape.

In California, the grape thrived, and at each mission, the friars and indigenous people worked side by side, tending the vines and making the wine. The wine was then used by the friars for Holy Mass, as well as for drinking at table and for making a fortified dessert wine, similar to port, that came to be known as angelica.

Serra passed away in 1784, but the vineyards he planted thrived for decades, with the Franciscans eventually selling wines to support their work, much as their European counterparts had done in centuries past. That trade came to an abrupt end between 1834 and 1835, when the Mexican government dissolved the missions. The friars asked to transfer the mission stations (and vineyards) to the indigenous residents and workers, who they believed were the rightful owners of the property. The government, however, rejected the friars’ proposal and instead allowed the land to be divvied up among wealthy politicians and landowners who ultimately exploited the native workers and neglected the vineyards.

Despite that neglect, the grapes from one vineyard, that of the San Gabriel Mission, just east of Los Angeles, have survived through the centuries. Those grapes, which can be traced back to the first grapes planted there by Serra, are once again being cultivated by a group of Southern California winemakers. Their hope is to produce the once-prized angelica dessert wine by this fall, when the mission celebrates the 250th anniversary of its founding by St. Junípero Serra, the father of California’s missions … and California’s wines.

Dom Pierre Pérignon and Champagne

Dom Pierre Pérignon was no saint. At least, not officially. Wine lovers, however, might argue that the Benedictine monk has earned a special place in heaven for his work at the Hautvillers monastery near the river Marne in France.

Born in 1638, in the eastern part of France’s Champagne region, Pérignon joined the Benedictines when he was just 19. For about a decade, he lived and served at the Abbey of Saint-Vanne at Verdun before, for reasons unknown to history, he transferred to the Hautvillers Abbey at Epernay. There, the monks regularly welcomed pilgrims who came to pray for the miraculous intercession of St. Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine, whose body was entombed there.

Like the pilgrims, the monks also sought St. Helena’s intercession, crediting her prayers with the excellent grapes they grew on their 100 acres of fertile land.

By 1670, Pérignon was the cellarer at Hautvillers and charged with managing the vineyard’s finances and administration. He also was responsible for making sure the monastery’s wine fetched the highest possible price. One way to do that was to improve the quality of the wines, so Pérignon undertook an overhaul of the entire winemaking process at the abbey.

He began by improving the wine cellars, digging deeper and wider cellars than any monks before him. He next began looking for a way to make the Champagne produced by the abbey appear red, instead of the more common pinkish-grey color (vin gris) that marked the Champagne of the 17th century. He succeeded at that by using grapes from old vines, with more tender skin. That method, however, only worked during particularly sunny years.

So, Pérignon next set out to find a way to make white wine from red grapes. He managed that through developing a new method of pressing his wines.

Dom Pierre Perignon, whose winemaking innovations gave us today’s champagne.

Pérignon’s innovations were paired with the careful selection and combination of grapes, developing new blends not only according to the flavor of individual grapes, but also according to the weather each year. His methods worked. By 1690, Hautvillers’ wines were famous, and by 1694, they were fetching prices so high, the monks decided to etch the amount on their wine press.

Pérignon wasn’t finished yet.

Thanks to the innovation of storing wine in glass bottles, which came into widespread use during his tenure at Hautvillers, Pérignon began paying special attention to the second fermentation that caused a bubbling effect in certain wines. His goal was to capture the wine at a particular moment of aeration and preserve those bubbles. The problem was that the bottle stoppers of his day—wooden plugs wrapped in oil-soaked hemp—made that impossible.

Then, one day, two Spanish monks came calling at the abbey and, while visiting with them, Pérignon noticed they were drinking water from bottles with stoppers made of cork. That set him to experimenting, and soon enough, Pérignon swapped his wooden plugs for cork plugs. By 1698, that switch made it possible for the Benedictine monk to produce the first great bottle of the sparkling wine the world now knows as Champagne.

Within two years, the Champagnes from the Hautvillers abbey were selling for twice as much as the very best still vin gris Champagnes had once sold, and within a decade, it was the preferred drink of kings, queens, and nobility throughout France and much of Europe.

Dom Pierre Pérignon died in 1715 and was buried in the abbey church of Hautvillers. There, a black marble slab and carved relief commemorate the Benedictine monk who singlehandedly changed the history of winemaking and wine drinking.

For centuries, the need for Liturgical wine led many religious orders to produce most of the world’s best wines.

Emily Stimpson Chapman is writing a new book about the past and present of Catholic winemaking in Europe for Marianist Press. It is due out in 2022.