Tina Greathouse ’11 knows what it’s like to be stretched between both ends of the caregiving continuum.

When she was eight months pregnant, the director of Student Academic Support Services at Franciscan University was sitting at her father’s bedside in a hospital intensive-care unit because her mother was too ill to be there. Later, after her child was born, she often had an active toddler running about while she was trying to administer intravenous medication or give her mother a bath.

Greathouse cared for both her parents for several years before their deaths, all while raising a family of four. Although she was often overwhelmed, she says she and her husband, Eric, prayed every night for God to lead them in what they were supposed to do.

“And we really feel like we did,” she says, adding that, looking back, she wouldn’t have changed anything. “The past three years were probably some of the most difficult in my life, but now that I’ve come through it, I see all of the blessings.

Asking for Help

As parents age, adult children like Greathouse often find themselves caring for their parents, managing medical appointments, medications, meals, and a host of other needs at a time when work and raising a family also drain their energy and resources. As a result, many feel “sandwiched” between their parents and other responsibilities, a situation that has spawned the term, “sandwich generation.” According to SeniorLiving.org, 47 percent of adults in their 40s and 50s now have a parent 65 or older while they are raising or supporting children. One in seven is financially aiding both parents and children.

Not surprisingly, many experience burnout as they try to care for those who gave them life.

For Greathouse, who began looking after her parents while they were still in their own home and later brought her mother into her home after her father died, asking for help was key. Even though she had support from her husband and older children, she got to the point where she had to reach out to her sisters, cousins, friends, and aunts.

“That was hard, and I know part of that is pride, but I’m so glad I did,” she says. “Everyone was willing to help, but they just didn’t understand I needed help until I asked.”

Just having someone sit with her mother for a few hours, especially during the last three months of her life, Greathouse says, gave her and her husband a chance to get away for dinner or even a trip to the grocery store.

“It was time alone where we didn’t have to worry and be on edge.”

Cathy Cich ’88, a nurse who took care of her mother in her own home before she had to be moved to an extended-care facility, had a similar experience.

“When Mom first started living with me, she had a baby monitor on her bed. I’d say if you need anything, ‘Call Cathy,’ … but I was exhausted. There were days when I hardly had any sleep whatsoever.”

Cich eventually wore down and had to ask for help from her sister, who began sharing caregiving duties with her.

Adult children, Cich says, must recognize that they need some time for themselves and, if they are married, with their spouses and children. “You can’t be 100 percent absorbed.”

A Voice in Decision Making

Cich says adult child caregivers also can exhaust themselves by failing to give their parents some autonomy by letting them do as much for themselves as they are willing and able to do.

“You want to allow them to have as much freedom of choice as you can give them.”

Dr. Christin Jungers, dean of Franciscan’s School of Professional Programs and a professor in the University’s Clinical Mental Health Counseling Program, says that freedom is especially important when decisions are being made about the care of elderly parents.

“If adult children can be aware of that need for autonomy and self-directedness, it could help them refrain from making decisions for their parents when they are still capable and wanting to do so,” Jungers says. “This helps to serve the whole person because it is a safeguard against an adult child’s concern and fear taking over and inadvertently undermining a capable parent’s free will.”

Jungers, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on older adults transitioning from home to assisted living, says she found that those who are not involved in decisions about where they live following a health crisis, for example, find the change more difficult. This is because, she says, the ability to make decisions and to be autonomous is a basic human need for happiness, human development, and growth.

In interviewing people for her dissertation, she found that stepping in and making decisions for an older adult without giving him or her the ability to choose often had a negative emotional and psychological impact, even though those decisions may have been motivated by concern and love.

Elderly parents also can lose their voice in decision-making because of stereotypes about older adults, Jungers says.

“People sometimes have a hard time distinguishing physical limitations from mental limitations. ‘Mom fell and broke her rib’ and now, without really thinking about it, caring loved ones can forget the parent still has her mental faculties about her and subsequently take over decision-making when it is not warranted.”

Cecilia McCarry, friend of Franciscan, celebrating her 94th birthday.

Dealing With Alzheimer’s and Dementia

However, a parent with dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease can present another set of challenges.

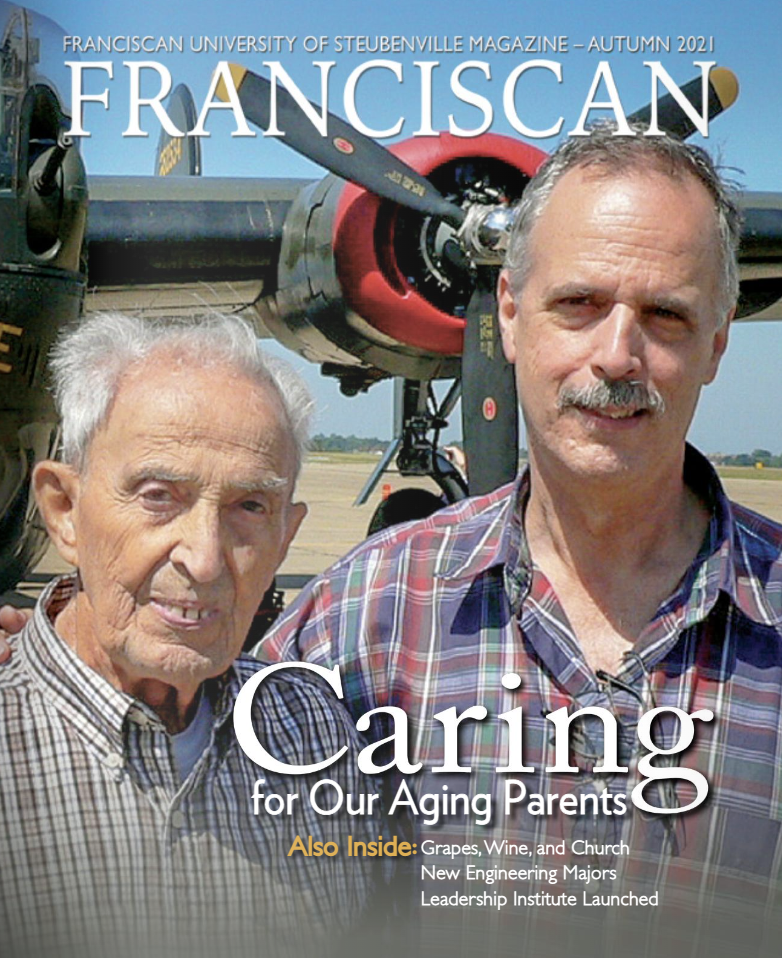

When Tom Sofio, public relations manager at Franciscan, assumed responsibility for his father after his mother died, he and his family realized how much his dad’s early-stage Alzheimer’s had been masked by his mother’s care.

“Suddenly, we’re with someone who doesn’t remember to eat,” Sofio says, adding that he also had to make sure his father brushed his teeth and washed his hands. “He was like another child, a younger child, but he was my dad … We had to kind of parent him in little ways.”

Over the next three and a half years, Sofio’s two sons took turns staying with their grandfather at his house at night. Then, each morning, Sofio’s wife, Therese, would take her father-in-law to Mass and afterward to their house to spend the day.

“He just became part of our meals and routine,” Sofio says, whether it was going to a sporting event or praying the Rosary each evening. Still, he adds, “It was a shock to have to do basic care and be attending to someone at a stage where your youngest two boys are in high school and your daughter is in college.”

The hardest part of caring for his father, Sofio says, was making sure someone was always with him.

“It altered our life, but when it was over, it was like, ‘Well, we did it,’ and we don’t even think about the times it was difficult.”

Tom Sofio with his father, Anthony Sofio.

Recalling the Blessings

What the family will never forget, he says, were the blessings that came from the time they spent with his father. Sofio says he got to know his dad again, and his children were able to learn about him in ways they might not have otherwise, whether it was his personality, his career in the aircraft industry, or his growing-up years in northern Michigan.

Additionally, he says, he thinks the experience taught his children compassion and likely was early training for being parents themselves.

“Son Ryan checked on Dad at night and played checkers with him. Son Justin took Grandpa on fishing trips and to his sports events. Older daughter Katie, a student at Franciscan during this time, often visited with him, looked at photo albums with him, took him shopping and on walks. So, the entire family chipped in with activities and ‘parenting the parent’ duties.”

Likewise, in her caregiving, Greathouse witnessed blessings emerge from what was often a trying time. For example, although she struggled watching her mother suffer with pain during her last months, she remembers the joy her 2-year-old daughter gave her grandmother. Also, the month before she died, her mother had asked Greathouse’s husband to pray with her.

“She was scared to die, but at the same time, she knew it was happening and accept it.” The prayer calmed her, Greathouse says, adding, “I think my mom died at peace, understanding that even though she didn’t know why she had to go through this suffering, the Lord had a purpose for it.”

Cich says caring for her mother, who had Alzheimer’s, gave her renewed empathy for the patients she saw in her hospice work.

“I was able to say, ‘I’ve been there. I know what you’re going through and it’s very difficult.’ It gave me more compassion in what I was doing as a nurse.”

Erin (Wiedenmann ’04) Pohlmeier with her dad, Charles Wiedenmann.

Take Advantage of Hospice Resources

As a now-retired hospice nurse, Cich encourages adult children caring for their parents to consider hospice care because of the resources available to them.

“So many people think it’s for when someone is dying, but hospice provides a world of support with nurses, aides, social workers, and respite care. It’s not a journey you have to make alone.”

Greathouse agrees.

“When Mom started hospice care, like a lot of people, I had the preconceived notion that it’s the end, and it’s not necessarily the end. For my mom, it was, but hospice often has patients with them for years.”

Her mother was admitted to hospice care for pain control, but Greathouse discovered a variety of other services were provided, including spiritual counseling and transportation.

“There were so many things I didn’t know were available that I wish I had known about sooner.”

Even when a patient dies, she says, the hospice her family used offers grief counseling for up to a year following the death.

Power of Attorney

Well before parents get to the end of life, Brenda Polk Garland ’10, a Michigan attorney specializing in estate-planning and elder law, recommends urging them to establish a medical power of attorney or patient-advocate designation. This, she says, can help avoid court involvement and can also help guide children or other decision-makers through whatever medical issues arise.

Garland also suggests setting up a durable power of attorney to enable someone to make financial decisions for an elderly parent in the event of an accident or enduring medical condition.

In many ways, Garland says, these are even more important than other estate-planning documents that deal with someone’s assets after death.

“Those do ease the burden for the family as to stuff, but rights are a more gnarly thing to navigate during one’s lifetime.”

“We knew we had to do this, that it was part of our duty. Faith teaches us to care for others, and it starts with your family.”

Ideally, she says, parents should take the initiative in drawing up such documents, preferably when they are making the transition into retirement.

“It doesn’t have to be expensive, but it does have to be specific to your state of residence,” she says, adding that, for those who aren’t ready to invest in an attorney, area commissions on aging can be a resource for connections to the local legal community and navigating Medicare and Medicaid.

Franciscan writer Jessica Walker with her 96-year-old grandma, Ruth Then, and family.

A Witness of Love

Despite the best of arrangements for the later years, however, there is often no way for adult children to be completely prepared emotionally for reversing roles and caring for their parents.

Greathouse says, for the most part, she was able to steel herself for her parents’ decline, but she says, “You’re never fully prepared. I don’t think anything could have helped more.”

For her and other adult children who are caregivers, faith is often a motivating and steadying influence.

“Love and care for others begins with family,” Sofio says. “Otherwise, you’re faking it. We knew we had to do this, that it was part of our duty. Faith teaches us to care for others, and it starts with your family.”

Adds Jungers: “In the family, when you tie meaning to the caregiving you’re doing, it becomes a witness of love and the dignity of life in its later phases.”

Caring for an older adult parent, she says, also can be a way to experience some solidarity with the challenges of the later years, with some of the pain and suffering that come with body and mind not working as they should and with death and dying.

“That gives us an opportunity to show deep compassion with our family member, and I think that’s a very Catholic thing.”

Judy Roberts writes from Greytown, Ohio.

Heavenly Helpers

When caring for your elderly parents, you are not alone. A host of heavenly friends stand ready to help you navigate the complexities of caregiving. Two saints in particular are said to have some special influence in this area: St. Jeanne Jugan, patron saint of the elderly, and St. André Bessette, patron saint of family caregivers.

St. Jeanne Jugan

Born in France in 1792, St. Jeanne Jugan grew up poor, helping to pay her family’s bills by working as a kitchen maid, nurse, and servant. Although she received two marriage proposals, she refused both. God was saving her for another work, she explained to her family; she needed to wait.

n 1839, at age 47, the waiting ended. That winter, while living in a small apartment with two other women, Jugan met Anne Chauvin, an elderly woman living on the streets. Jugan took the woman into her apartment, giving Chauvin her bed.

Soon, Jugan convinced her roommates to take in more women. Within two years, they acquired a convent that could house 40 elderly women. They also acquired more helpers and founded, the Little Sisters of the Poor. Jugan wrote their first rule and was elected as their first mother superior.

The order grew rapidly, and by 1879, more than 2,400 Little Sisters of the Poor were serving the elderly across Europe and North America.

Like so many caregivers, however, Jugan’s work went unappreciated.

In 1850, the priest who had been appointed superior general of the congregation, Father Augustin le Pailleur, forced Jugan to step down as mother superior and sent her out to beg for the order.

She did that gladly. But, Father le Pailleur began presenting himself as the order’s founder and forbade the first sisters from acknowledging Jugan as their founder. Then, in 1852, he sent Jugan to the Little Sisters’ motherhouse and ordered her to end all contact with friends and benefactors.

Jugan remained confined there for 27 years, until her death in 1879.

In 1890, the Vatican began an investigation of Father le Pailleur, eventually forcing him into retirement. Jugan was canonized 119 years later, in 2009, and the Little Sisters of the Poor credit her patient suffering, in part, with their success.

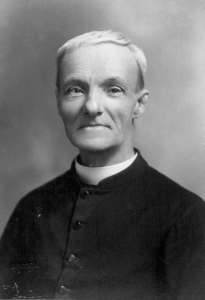

St. André Bessette

St. André Bessette (baptized Alfred) understood affliction from the inside. Born in Quebec in 1845, the eighth of 12 children, Bessette grew up in poverty. He lost his father when he was 9, his mother when he was 12, and four of his siblings during his childhood. Many were amazed Bessette didn’t join them. His chronic ill health made earning a living almost impossible. Bessette tried his hand at farming, shoemaking, blacksmithing, baking, and working in a factory but failed every time.

Finally, at age 25, Bessette’s pastor recommended that the pious young man try religious life. He sought admission to the Congregation of the Holy Cross in Montreal and was accepted as a novice. A year later, however, the congregation asked him to leave, citing his chronic ill health. This time, however, the bishop of Montreal intervened, and urged the congregation to find Bessette a place. So, they appointed him doorkeeper at the College of Notre Dame in Montreal.

Bessette crossed paths with hundreds of people each week. Inevitably, they would tell him their troubles, and he would respond by telling them to turn to St. Joseph. In his free time, Bessette visited the sick, anointing them with oil from the chapel and asking St. Joseph to intercede for them.

Soon, accounts of miraculous healings surfaced. As news of the holy doorkeeper spread, Bessette gave up his work at the college and did nothing but meet with the sick and afflicted. Eventually, he needed four secretaries to help him deal with the 80,000 letters that arrived annually.

In 1904, Bessette began raising money to build a chapel to honor St. Joseph. Although he never lived to see it completed, the Oratory of St. Joseph in Montreal is now Canada’s largest church. Brother André Bessette became St. André in 2010.

Prayer of the Caregiver

As generations of caregivers have done before me,

St. Brother André, I am coming to seek you out;

Be my patron saint and guide.

Give me the stamina I need to accompany

the person under my care.

Clear my mind when it’s time to make important decisions.

Show me how to bring compassionate relief,

so that everything takes place with respect.

St. Brother André, I surrender my fatigue to you.

Please give me resilience

in the face of long-term illness and suffering.

Help me to place my ailing relative in God’s hands.

Teach me to give of myself out of love,

free from self-interest. Safeguard me from exhaustion and isolation;

Be my patron saint and guide. Amen.

Esteeming Our Elders

St. John Paul II on the honor due to older people.

“Why then should we not continue to give the elderly the respect that the sound traditions of many cultures on every continent have prized so highly? For peoples influenced by the Bible, the point of reference through the centuries has been the commandment of the Decalogue: ‘Honor your father and mother’…

“Honoring older people involves a threefold duty: welcoming them, helping them, and making good use of their qualities. In many places this happens almost spontaneously, as the result of long-standing custom. Elsewhere, and especially in the more economically advanced nations, there needs to be a reversal of the current trend, to ensure that elderly people can grow old with dignity, without having to fear that they will end up no longer counting for anything. There must be a growing conviction that a fully human civilization shows respect and love for the elderly, so that despite their diminishing strength they feel a vital part of society. Cicero himself noted that ‘the burden of age is lighter for those who feel respected and loved by the young.’

“Furthermore, while the human spirit has some part in the process of bodily aging, in some way it remains ever young if it is constantly turned toward eternity. This experience of enduring youthfulness becomes all the more powerful when to the inner witness of a good conscience is joined the sympathetic concern and grateful affection of loved ones. …

“We are all familiar with examples of elderly people who remain amazingly youthful and vigorous in spirit. Those coming into contact with them find their words an inspiration and their example a source of comfort. May society use to their full potential those elderly people who in some parts of the world—I think especially of Africa—are rightly esteemed as ‘living encyclopedias’ of wisdom, guardians of an inestimable treasure of human and spiritual experiences. While they tend to need physical assistance, it is equally true that in their old age the elderly are able to offer guidance and support to young people as they face the future and prepare to set out along life’s paths.

“While speaking of older people, I would also say a word to the young, to invite them to remain close to the elderly. Dear young people, I urge you to do this with great love and generosity. Older people can give you much more than you can imagine. The Book of Sirach offers this advice: ‘Do not disregard what older people say, because they too have learnt from their parents’ (8:9); ‘Attend the meetings with older people. Is there one who is wise? Spend time with him’ (6:34); for ‘wisdom is becoming to the elderly’ (25:5).”

—St John Paul II, Letter to the Elderly, October 1, 1999, Nos. 11-12