If anyone told me 30 years ago that one day, I would spend my time writing and speaking in defense of the Catholic Eucharist, I would, at first, have been confused. I didn’t even know what the word “Eucharist” meant— we didn’t use that term in my Calvinist tradition.

Secondly, once it was explained to me, I would have been horrified! I belonged to a Christian group that—at least officially—was about as opposed to the Catholic Church and especially the Mass as you can imagine.

I come from a line of Dutch Calvinist pastors (think Presbyterians with wooden shoes and windmill cookies), and I felt called to be a pastor myself. Dutch Calvinism is a very intellectual Christian tradition, and unlike many American Protestant groups, we had extensive doctrinal statements called creeds and “confessions.”

One of the doctrinal statements I was required to affirm—along with many others—was that the Catholic Mass was a “condemnable idolatry.” The logic was this: in the Mass, bread and wine (mere creations) were worshiped as God. Worship of the creation is idolatry.

Therefore, “the Mass, at bottom, is nothing other than a denial of the one sacrifice and sufferings of Jesus Christ, and a condemnable idolatry” (Heidelberg Catechism, Q&A No. 80).

I don’t know of a more forceful rejection of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist in any other Protestant theological statement.

So that is what we thought of what I now believe to be the “source and summit” of the Christian life.

But God had other plans for me and began to move me toward the Catholic Church in ways I didn’t expect.

While I was working as a pastor in a downtown mission church in western Michigan, many of my Protestant convictions began to crumble. I began to doubt “salvation by faith alone” as I pondered many Scriptures that contradicted it (e.g. Matt. 7:21) and also saw the bad pastoral effects on people’s lives.

Many took it to mean their moral life didn’t ultimately matter to their salvation, and as a result, they fell into a moral cesspool that ruined their lives.

I also began to doubt “the Bible alone” or sola scriptura, because in my experience, no two Protestant pastors or theologians interpreted the Bible in exactly the same way.

How could we ever have the unity Jesus so clearly wanted (see John 17:11) if we could never agree on what God’s Word meant?

About this time, I started applying to graduate schools to do a doctorate in Scripture. I got accepted to the University of Notre Dame, which attracted me because of its ecumenical theology faculty: Jews, Catholics, and Protestants all taught there, including some from my own theological tradition (Calvinists).

I moved my family to Notre Dame to begin my doctorate in Old Testament without the slightest desire to become Catholic.

However, one of the first men I met on campus was a fellow doctoral student who had three qualities I never thought I’d find in one person: he was highly intelligent, full of the Holy Spirit, and Catholic!

I could not understand this. If he was so smart, and full of the Holy Spirit, would he not surely recognize the Catholic Church as a false church and so leave for the green pastures of, say, Calvinism?

I began to get lunch on a regular basis with Michael in the hopes of showing him the truth or at least figuring out how he could reconcile Catholicism with a true relationship with Jesus.

I began by showing Michael all the Scriptural disproofs of Catholicism—like Matthew 23:9, “Call no man on earth your father …”—but when I did so, Michael responded in a way I thought very unfair. He answered with Scripture!

I had never encountered such a thing before: someone quoting Scripture to defend the Catholic Church!

He pointed out, for example, that St. Paul tells the Corinthians, “I became your father in Christ Jesus” (1 Cor. 4:15), so Jesus could not have meant that statement in some literalistic way.

In fact, Michael had a biblical response for almost everything I could think of. We debated for weeks and even months, and I realized he could mount a good scriptural defense of the Catholic Church.

But one thing he could not convince me of was the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. No matter how many passages of Scripture he pointed out that identified the Eucharist as Christ’s body (Matt. 26:26) or flesh (John 6:54), it did not move me—“God also calls himself a Rock (Ps. 18:2),” I thought to myself, “and that is not literal.”

At this point in our discussions, Michael suggested we start reading the Church Fathers together, especially the earliest, the “Apostolic Fathers” who had known the Apostles personally.

I was intrigued, because I had never known we had any extra-biblical writings from men who knew the Apostles personally. And honestly, I was convinced that in reading them we would discover them to be Calvinists, because—for all my doubts about Protestant principles—I still could not shake the conviction, so long bred into me, that some form of Calvinism was the original faith of Christianity.

So, I began reading the letters of one of the earliest Fathers, Ignatius of Antioch. He wrote in about AD 106—a mere 10 years after the death of St. John the Apostle, too little time for confusion and legends to arise, and therefore, a reliable witness to what the Apostles actually taught.

Imagine my surprise, then, as I began running into very Catholic-sounding statements as I read through his letters—things like “Wherever the bishop is, there is the Catholic Church,” or “Only that Eucharist is valid which is authorized by your bishop.”

But the real “kicker” was this: At the end of chapter 6 of Ignatius’ Letter to the Smyrnaeans, he warns them about heretics who “refuse to confess the Eucharist to the flesh of our Savior Jesus, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, in his goodness, raised up.”

What!? I read that sentence over and over, and got a sinking feeling in my stomach—“There’s no way to get a symbolic interpretation out of what he is saying.”

I looked it up in the original Greek, where it is even clearer: He is saying that the Eucharist is not simply “Jesus” in some spiritual sense, but rather the same flesh that suffered for our sins and was resurrected.

There could scarcely be an earlier or more resounding affirmation of the Real Presence!

I began to think of the implications of this. Surely Ignatius could not have gotten confused in the short 10 years since the death of John—therefore, he must have received this from John. That, in turn, sheds a lot of light on what John’s Gospel means in John 6:54 and elsewhere.

It dawned on me the significance of what Michael had pointed out: The plain sense of all the New Testament passages on the Eucharist were simply that it was his “body” or his “flesh.”

At this point, I was extremely nervous, but I still held onto this thought: Perhaps Ignatius of Antioch was an outlier, the only Father who says this. I began to scan through collections of the Church Fathers for their statements on the Eucharist and soon discovered, No! Ignatius is not an outlier!

There is a consistent chain of testimony in the Fathers about the Real Presence. I’ll just cite one of the most important, St. Augustine, who is universally respected by Protestants and Catholics alike. St. Augustine says Jesus held his body in his own hands at the Last Supper. Further, he says, it is not a sin to worship the Eucharist, rather it is a sin not to worship the Eucharist!

That was directly contrary to our Calvinist doctrinal statements, which was ironic since we regarded Augustine as our intellectual father, a kind of proto-Calvin.

Within about a day and a half of frantic research and thinking, I realized the Real Presence was as well-attested or better-attested in the Scriptures and the Fathers as any central Christian doctrine, and already by the first post-apostolic generation of the Church, it was a touchstone of orthodox Christian faith.

If the Scriptures teach it and the Fathers received it, who am I—at a distance of 2,000 years—to dispute it? Is it the case that Jesus can’t make the Eucharist into his flesh? Certainly not!

Whatever he says, must happen, since he is God. When God says, “Let there be light,” there is light.

It occurred to me that Jesus had to be careful in what he said, because his word had creative power. So, when he says in the Upper Room, “This is my body,” without further qualification it would have been impossible for that bread not to change!

So, to keep a long story short, within about 36 hours of reading Ignatius of Antioch, I knew I would have to become Catholic.

If Jesus was really present in the Eucharist—as the Scriptures and the Fathers taught—that made all other theological disputes pale in comparison. If Jesus was really present in the Eucharist—and only the Catholic Church had stayed faithful to this teaching and practice—then I had to become Catholic if only to be close to the Eucharistic Jesus!

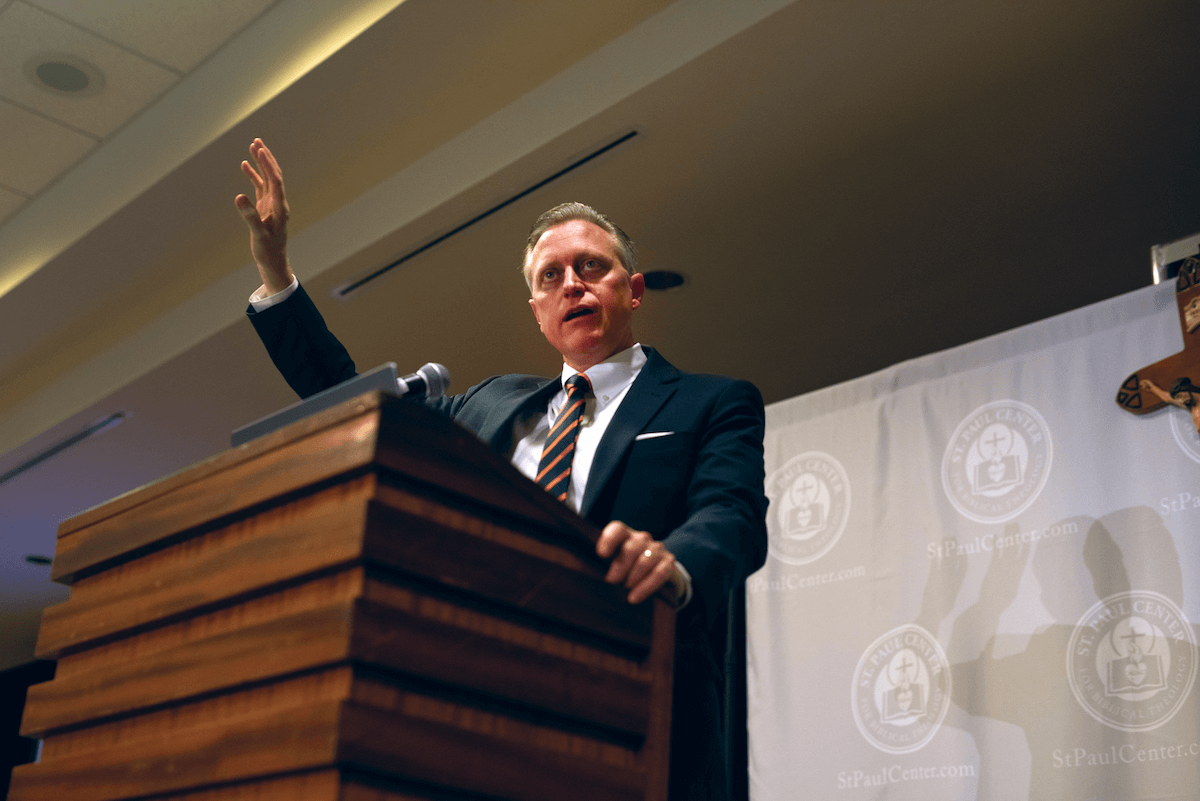

Dr. John Bergsma, professor of Scripture

I have been Catholic now for 22 years, and I still think this argument is compelling.

When I encounter non-Catholics who are open to talking about faith matters, I always bring up the Eucharist first and ask what they think about it. In my experience, very few non-Catholics have ever looked at what the Fathers said about it, even those non-Catholics who profess to respect the Fathers and be faithful to their teaching.

When I was a kid, the U.S. orange growers launched a nationwide ad campaign whose slogan was “Orange Juice— it’s not just for breakfast anymore!” The point was, let’s get out of the mental box that says orange juice can only be drunk for breakfast.

But what I want to say is: “The Eucharist—it’s not just for Catholics anymore!”

Not in the sense that we should give open Communion even to those not in communion with the Catholic Church. Rather, we need to think of the Eucharist not as a “Catholic thing” but a “Christian thing” that is integral to any true Christianity.

Methodists, Lutherans, Pentecostals—all baptized Christians are called by the Scriptures and the teaching of the Fathers to partake of the Eucharist, which according to the words of Jesus himself simply is the New Covenant promised by Israel’s prophets.

And since only the Catholic Church retains the fullness of authority to confect the Eucharist, that means all Christians need to take steps to reconcile themselves to her authority and teaching and join us at the banquet table of the Lord!

Dr. John Bergsma is professor of Scripture at Franciscan University as well as a prolific writer and speaker.