The Christian life creates an uncomfortable paradox between continuity and change. The Scriptures assure us Our Lord doesn’t change: “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever” (Heb. 13:8). We, however, are imperfect and are called to transformation to become more like him (see Rom. 12:2). This requires personal change and transformation. The same paradox exists for Christian institutions: To fulfill an unchanging mission, ongoing transformation is necessary.

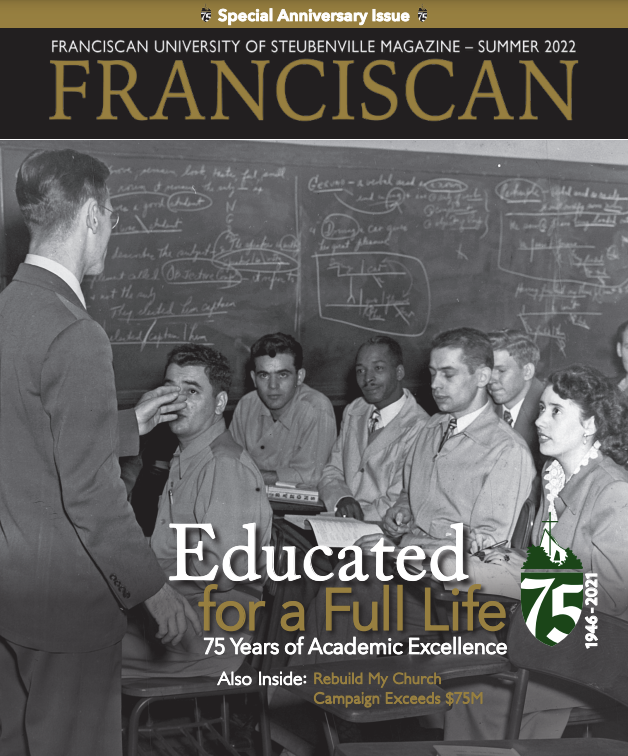

From its founding 75 years ago, Franciscan University has remained committed to serving Christ and his Church. That commitment inspired the Franciscan TOR friars to say yes to Bishop John King Mussio when others said no to establishing a college. Although the phrasing has varied, since first admitting students in 1946, the College of Steubenville has stayed committed “to educating, evangelizing, and sending forth joyful disciples.”

Students who arrived at the College in the late 1940s and early 1950s were relatively well catechized and firm in their faith, so the school had less need for an explicit focus on evangelizing them. By the time Father Michael Scanlan, TOR, arrived on campus as president in 1974, however, students had begun to change.

American youth were told to question all authority and to reject all established institutions, including the Church. While faith-filled Catholic students still enrolled at the College, dwindling Mass attendance, a developing drug culture, and increasing student loneliness and depression indicated a need for institutional change. To continue our founders’ mission, the College needed new programs and practices. This intentional focus on evangelizing students took the form of student households, Festivals of Praise, and a revitalization of the sacramental life to replace the culture of death with Christian hope.

After much effort and innovation, the renamed Franciscan University experienced a restored Catholic culture. But even as more committed Catholic students were finding a spiritual haven here, the militant secularization of culture accelerated elsewhere.

Many Catholic schools responded by downplaying, or even ignoring, Church teachings that were out of sync with the secular agenda. While many argued for soft-pedaling Catholic teaching by shifting focus to issues most in agreement with the secular culture, there is little evidence this ingratiated the Church with secularists. Indeed, they regularly portrayed the Church as outdated and irrelevant. More importantly, this self-limiting trend in Catholic education left generations of Catholics poorly catechized. (My own religious education classes, for example, taught me much about the evils of the war in Vietnam and about the need for stewardship of the earth but left me unformed in major areas of Catholic teaching.)

Franciscan University again responded by providing more overt evangelization and catechization—especially in the classroom. Faculty reworked the core curriculum to provide the theology and philosophy prescribed in Ex corde Ecclesiae. They also countered the rising relativism of knowledge with required core courses on the history of Western civilization, the great works of Western literature, and the principles of the American founding, along with a science requirement and the University’s first-ever math requirement.

Ironically, and dangerously, the modern world’s rapid moral decline has been accompanied by equally dramatic technological and scientific advances. Because of this, Franciscan University has dramatically improved in the sciences, while developing new expertise on the ethics of scientific research and technological innovation. We signed affiliation agreements so our students could find slots in doctoral programs in pharmacy, physical therapy, and medicine. We introduced new majors, such as software engineering and mechanical engineering. Existing majors have added new technology into their courses such as the Nursing Department’s considerable and growing expertise using manikin patient simulators.

In sum, to remain academically excellent and passionately Catholic, to continue “to educate, evangelize, and send forth joyful disciples,” has involved much change at Franciscan University over the first 75 years and will continue to require difficult and challenging transformation in the next 75 years.

Dr. Daniel Kempton serves as professor of political science and vice president for Academic Affairs at Franciscan University.