Should educators and students embrace artificial intelligence (AI)? Is it a tool to be used or a sci-fi technology to be feared? Could AI make the traditional on-campus college education obsolete?

Since OpenAI released ChatGPT in 2022, questions like these and discussions about AI’s benefits and risks have ramped up at colleges and universities around the world, including Franciscan University of Steubenville.

What Is AI?

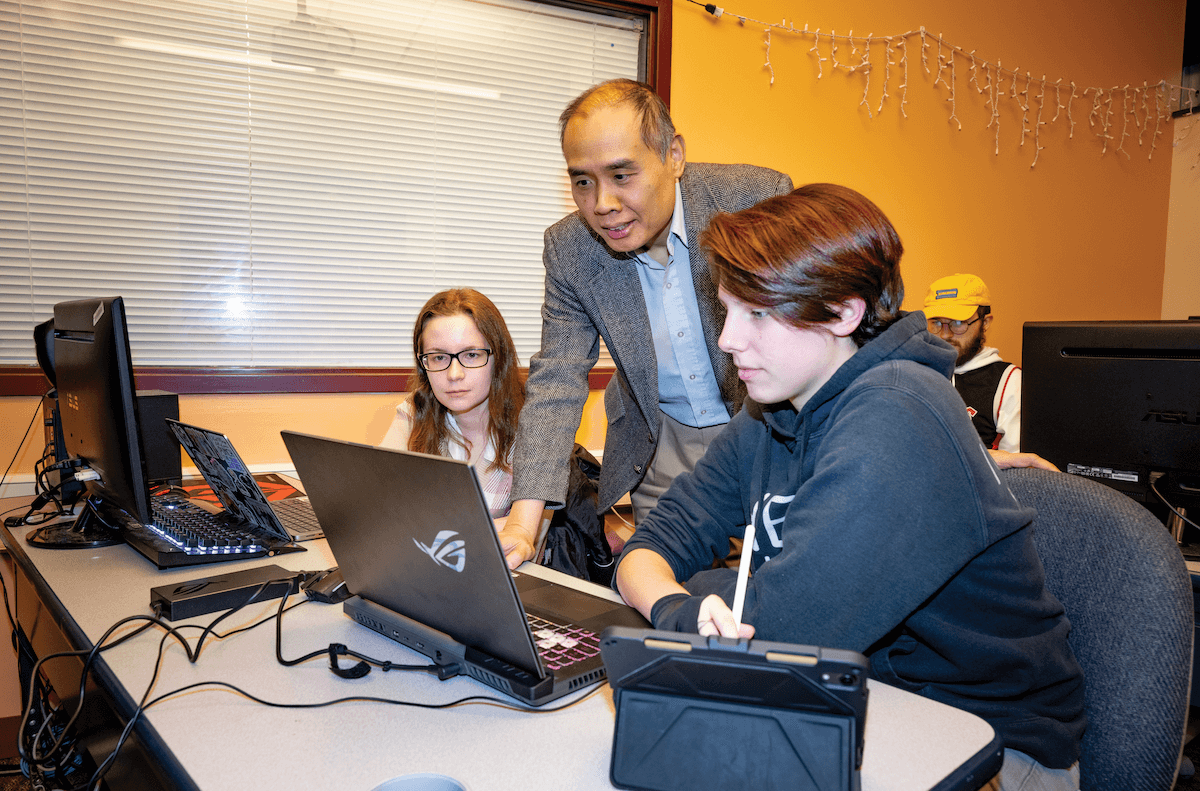

Dr. Christopher Davis, past director of Information Technology Services at Franciscan University, says most people hold Hollywood-inspired misconceptions about AI.

“Everyone thinks of movies like The Matrix and The Terminator, where machines come alive and start to think and become sentient beings. The term AI is actually much broader than that,” he says.

Anyone who uses spellcheck in Word, Grammarly to edit, Rev/Temi to transcribe, Lightroom to touch up photos, or Google for searches already benefits from AI technology. Broadly speaking, AI is a technology that creates computer applications and programs like these that can learn how to do certain human functions and make simple decisions.

The difference between traditional AI and generative AI (sometimes called creative AI) is this: “Traditional AI can analyze data and tell you what it sees, but generative AI can use that same data to create something entirely new” (Bernard Marr, Forbes, July 24, 2023).

Some Benefits . . .

AI has made research much easier and more efficient for professors and students through language model chatbots such as Google Bard for answering questions and writing quizzes, and ChatGPT for summarizing texts.

Dr. Eugene Gan, professor of interactive media, communications, and fine art at Franciscan, says, “It is a wonderful tool for research, as a jumping off point to bring together wide data sets.”

Gan and Davis offer several other benefits to using AI in education.

1. Personalized Learning

Gan says, “AI can adapt to individual learning styles and pace, providing personalized learning experiences for students. This tailoring of educational content can help students grasp concepts more effectively, addressing their specific strengths and weaknesses.”

2. Easy Access

“It allows all instructors, regardless of area of concentration, to use modern technology in their teaching that has a fairly low learning curve,” Davis says.

3. Efficiency and Automation

“AI tools can automate administrative tasks, grading, and other routine processes, allowing educators to focus more on interactive and engaging aspects of teaching,” Gan says.

4. Data-Driven Insights

Gan also appreciates that AI can analyze vast amounts of data generated in the learning process to identify patterns, trends, and areas for improvement.

“This data-driven approach enables educators to make informed decisions about curriculum design, teaching methods, and student support, fostering continuous improvement,” he says.

. . . And Some Risks

Whenever new technologies emerge, there’s always some pushback. When the internet became popular in the 1990s, Davis says some people thought it marked the end of higher education. Academics then, as now, worried students would plagiarize because they had access to the World Wide Web.

“Of course, people cheat, and they find creative ways to do it, but the majority of students are honest, and they want to learn,” Davis says.

However, maintaining academic honesty is a real concern, motivating faculty to modify their teaching methods. While students can use Bard and ChatGPT to cheat, educators can also use them to help detect cheating.

Beyond cheating, Davis and Gan recognize some additional concerns about AI use.

1. Privacy Concerns

Gan says, “The use of AI often involves collecting and analyzing significant amounts of personal data.”

And Davis warns, “As you use these tools, you need to read the terms and conditions about what they do with your information. Look at your privacy settings in Google because you can turn a lot of that off.”

2. Loss of Human Connection

While AI can enhance certain aspects of education, Gan explains, “Building relationships, understanding individual emotional needs, and addressing non-academic challenges are vital components of the learning experience that AI may not be equipped to handle effectively. Overreliance on AI could potentially lead to a lack of empathy and understanding in the educational process, impacting the overall well-being of students.”

AI Is Just a Tool

Davis says, overall, it’s critical to understand AI capabilities “instead of just being afraid of it or pretending it doesn’t exist.”

“What’s important to remember is AI is just a tool that’s trained by human beings,” Gan tells his students. At Franciscan, professors have a choice about how much they use AI in the classroom. Gan—who helped launch Franciscan’s multimedia concentration to prepare students for careers in designing video games, special effects, animation, videos, and more—introduces students to AI in his Digital Photo Compositing and Fine Art class.

Senior Lucy Backman says she learned about AI by using Adobe Photoshop.

“We either take pictures of our own, or we find them on the internet,” she explains. “Then using all the tools we have in Photoshop, we composite different images together to create one cohesive image.”

Students may use AI to create their art, but they are not required. But Gan also asks students to document the steps they take to create their photographs.

“He encourages us to create a short video at the end of our project and to toggle on all the layers we created to show that we completed the process on our own,” Backman says.

For her, AI’s purpose is to simplify intermediary processes.

She says, “AI shouldn’t eliminate the creative process, which includes brainstorming and finalizing.”

Don’t “Idolize” AI

When Gan completed his research honors thesis at Carnegie Mellon three decades ago, one of his projects was to have AI create artwork based on expressions he manually fed to the computer.

“It was a surreal experience because, after multiple iterations of training this AI, it was creating art pieces I approved of,” he recalls. “The surreal thought at that time was, ‘Did I just somehow record a part of me into this ether?’”

With the latest version of generative AI, that unreal feeling has persisted for Gan. Those AI art pieces he made in the 1990s took considerable effort, but today, he can create the same content in seconds.

The most significant danger in AI technology is allowing it to think for us, he says. Our culture shouldn’t view AI as a god or an idol.

“I’m witnessing folks on radio shows and forums treating AI like a god—magical, all-knowing. AI is a tool that can support our human dignity, but when we allow it to replace us, when we idolize, that’s the danger. We become less human,” says Gan, author of Infinite Bandwidth: Encountering Christ in the Media.

Bigger Impact Coming

AI can be expected to go beyond doing mundane tasks as it becomes more sophisticated.

Gan says, “We have to reevaluate how we are forming ourselves, our students, the young. I am very cautious about my own children using technology, even using their phones as a crutch. For example, I want them to memorize things.”

He also advises people to pray for discernment before and after they go online because “you cannot trust your eyes or ears. Photographs, audio, and videos are easily altered with AI.”

He adds, “AI is certainly affecting all of us in every aspect of life, and it will all the more, in the coming months and years.”

Despite the potential downsides to AI, both Gan and Davis believe AI is ultimately just a technology humans created. Humans will decide whether or not it becomes something good or bad.

Gan says Catholics have been—and still are—leaders in education, and historically, Catholics have been open to new trends in technology, which he calls “gifts of God.”

Gan recommends, “We need to continue to step into that role of being leaders in education and to lead society in how to best use AI.”

Lori Hadacek Chaplin writes from Idaho.