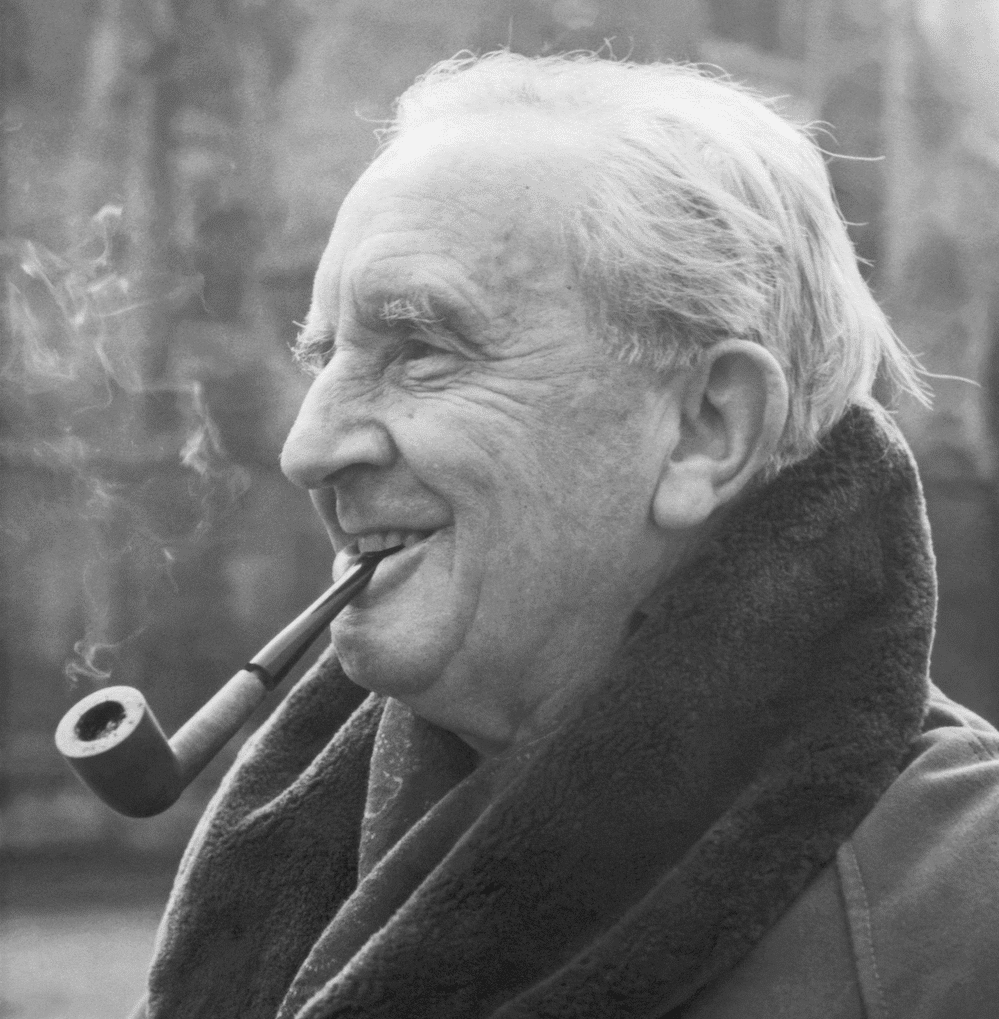

Franciscan University held A Long-Expected Party: A Semicentennial Celebration of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Life, Work, and Afterlife on September 22-23, 2023. Organized by Franciscan English professor Dr. Ben Reinhard, the conference centered on the beloved Lord of the Rings author and featured J.R.R. Tolkien scholars, including Dr. Holly Ordway, the Cardinal Francis George Professor of Faith and Culture at the Word on Fire Institute and Visiting Professor of Apologetics at Houston Christian University. Her newest book, Tolkien’s Faith: A Spiritual Biography, was released on September 2, the 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s death. Ordway sat down recently with Franciscan Magazine to discuss Tolkien’s faith, the enduring appeal of his work, and more. Here’s what we learned.

In Tolkien’s Faith: A Spiritual Biography, you write that Tolkien’s faith “could not be disentangled from his art.” How did his faith inform his fiction?

It was really fundamental to it. He says The Lord of the Rings is “a fundamentally religious and Catholic work.” That quote is often misunderstood or oversimplified to look for Gospel parallels, but he’s very clear that there’s no allegorical element whatsoever. The religious and Catholic element is, as he put it, in “the story and the symbolism.”

His faith shaped his entire approach to writing, and his understanding of creativity in general. He felt that being able to write, being able to create, comes about because he is made, as he put it, “in the image and likeness of a Maker.” It’s because God is creative that human beings are able to be creative in turn, and that’s really fundamental to his self-understanding as a writer.

What can we learn from Tolkien’s faith journey and his struggles?

He did have struggles; his life was not just easy coasting. This is a misperception a lot of people have about Tolkien. They think of him as he was in the end of his life: a mature, well-grounded Catholic man. … After the Great War, Tolkien goes through a period of which he says, “I almost ceased to practice my religion.” Now, “almost ceased” means he didn’t actually give it up, but it was absolutely a barren stretch for him. He said he felt a great longing for Christ in the Blessed Sacrament, but for whatever reason, he did not have that longing satisfied.

He persevered, and we see in his mature writings that he’s very emphatic about the importance of the will in matters of faith. Faith isn’t just about emotions. He knew very well that those feelings might go away. But to know objectively that Christ is present in the Blessed Sacrament, that was really bedrock for him. … For Tolkien, there’s that firmness of knowledge and will. The assent of the will is really critical and that allows him to stay in his faith, even when his emotions and experiences were pulling him in different directions.

You mention in your book that you studied Tolkien as an agnostic undergraduate, an atheist graduate student, and later taught his works as a Protestant Christian. How did your views of his writing and faith change throughout your own spiritual journey?

I always loved Tolkien; I read The Hobbit by the time I was 8. As I got older and became an atheist, I still loved Tolkien. He was always kind of a witness and a challenge to me. I never doubted he was an amazing writer, yet there was a whole aspect of his life I didn’t want to know about. Later on, after I had my PhD, I found myself returning to the fact that all my favorite writers were Christian, and I thought Christianity was ridiculously stupid. But my favorite authors were anything but stupid. They did not permit me to simply dismiss Christianity. And that was a big part of what led me to investigate and become Christian. Tolkien, all along, gave me a vision of the beauty of what it is to be a Christian, and ultimately, to be a Catholic.

Why do you think Tolkien’s fiction holds meaning for such a diverse audience?

They’re great stories. They’re accessible to such a wide audience, in part, because he makes his faith implicit rather than explicit. It’s in the fundamentals; it’s not overt in a way that could be off-putting. His themes resonate with us: Virtue, self-sacrifice, pity, mercy, and friendship are all rooted in Tolkien’s Christian values, but they are also appealing to any human being.

One of the reasons The Lord of the Rings is so attractive is it shows that what we do matters. The hobbits are the most humble figures, yet it’s their decisions that end up saving Middle-earth. … That’s really encouraging; it’s the kind of expression of Christian virtue that’s accessible to people regardless where they are in terms of their acceptance of Christianity.

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings garner a great deal of attention. Are any lesser-known works as worthy?

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings gain most of the attention because they are his master works. The Lord of the Rings is his magnum opus, so it’s right and proper that it gets the most attention. The Hobbit is not at the same level, but it is still a polished book. Tolkien’s shorter works are often overlooked; his essay “On Fairy-stories” is of distinction, and his short story “Leaf by Niggle” is an absolute gem. I would recommend it to every fan of Tolkien.

Tolkien’s works are filled with symbols. Is it fine to read Tolkien simply on a surface level?

Absolutely, and I think Tolkien would have said yes. He sat down to write a really good story. If you have to hunt for symbols to get anything out of it, it’s not a good story. All the great writers, from Shakespeare to Dickens to Austen, all have that quality. You can enjoy Shakespeare for the stories; you can enjoy Jane Austen for the romantic comedy. And that’s the entry point for a lot of people. If that’s where you stay, you have enjoyed a really good story. But there’s more if you come back to it. There is a beautiful, additional level for anyone who wants to see it.

Do any modern writers approach his level of genius?

I really don’t think so. But that’s asking a lot, because how many Shakespeares do we have?

Why should we read Tolkien in the 21st century and gather to study his works?

At this point, Tolkien has proved himself to be a writer for the ages. I firmly believe that in 200, 300, 500 years, people are going to be studying Shakespeare, Chaucer, Dickens, Tolkien—he’s going to be up there with those authors because he is that good.

He’s a master of the English language. He’s a tremendously expressive writer. He has such a nuanced understanding of human experience. His works speak to the truths about human nature and our reality. … Also, as I’ve learned when working on Tolkien’s Faith, he was a genuinely interesting and fundamentally good man. Not a perfect man; he had his flaws, and he’d be the first to admit it, but a very good man, friend, colleague, husband, and father. Learning about his life, his thought, his spirituality helps us appreciate his writing more deeply, to understand it more fully.

There are great depths to his work. And gathering together to talk about all these things, to enjoy what he has written, is fellowship of a kind I think Tolkien would very much approve.