Four Franciscan University alumni who are currently pursuing doctorates agreed to answer my questions and my curiosity: What are you studying? Why? What are you going to do with it? And: How did Franciscan prepare you for doctoral studies?

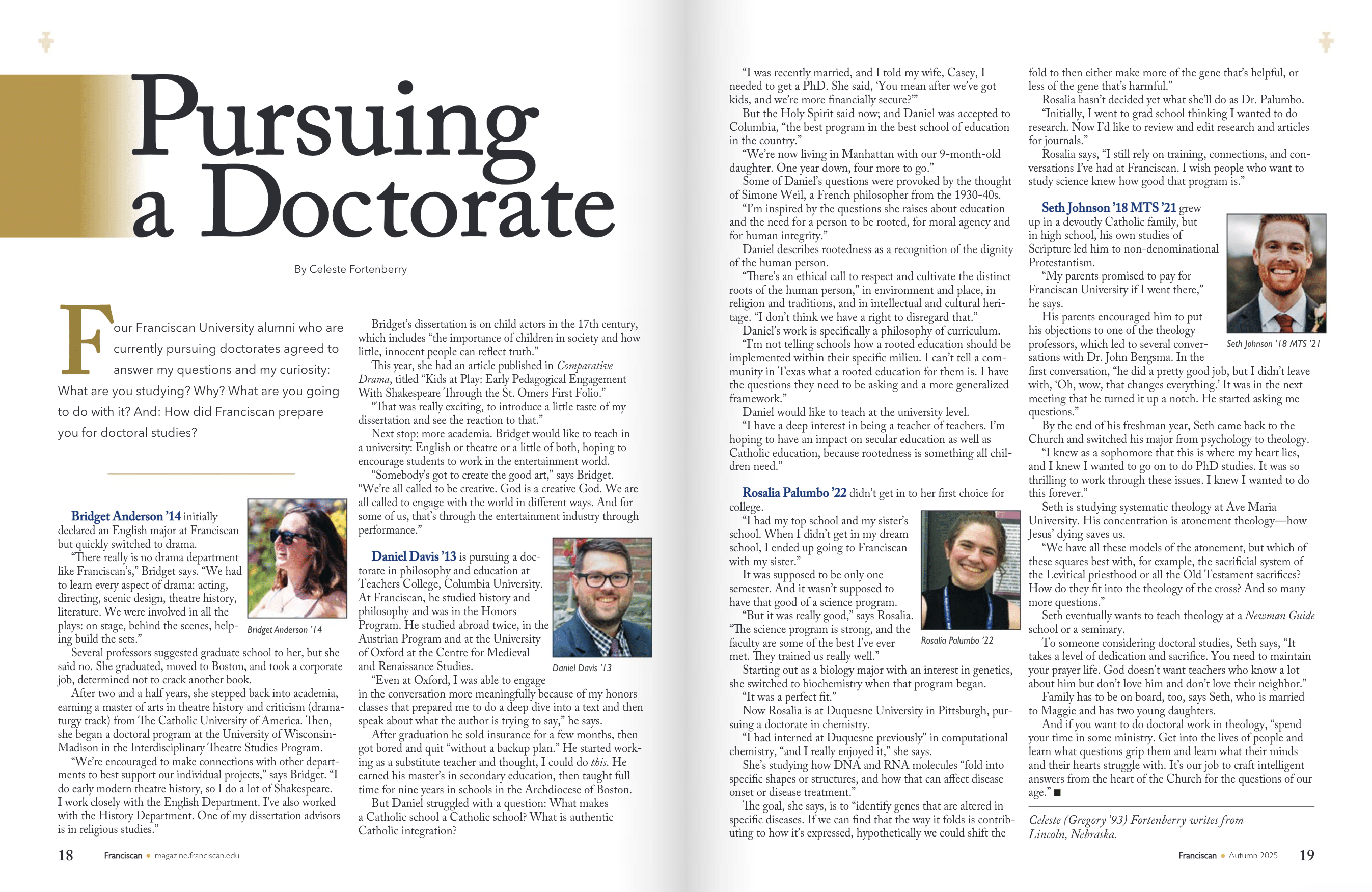

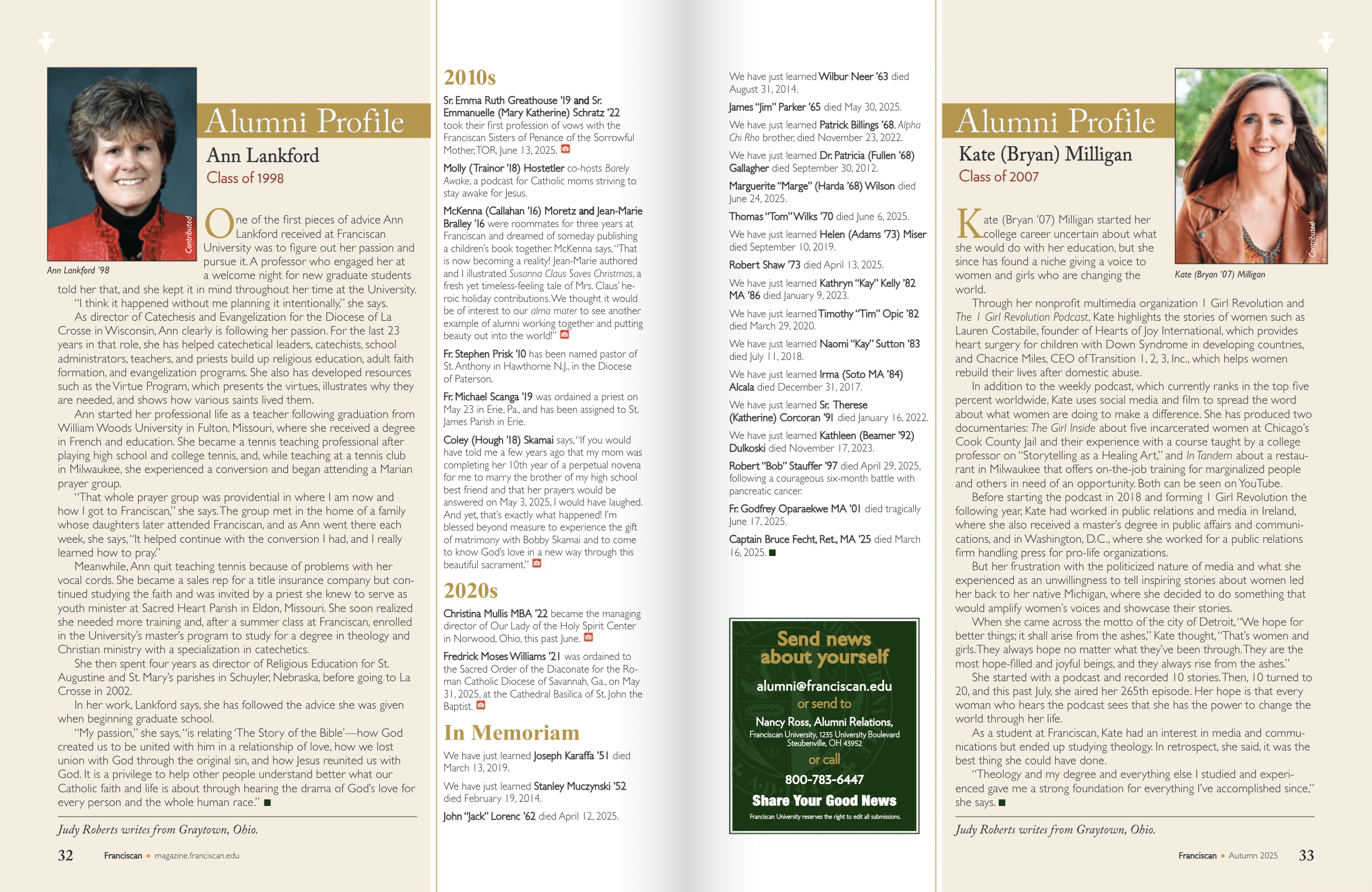

Bridget Anderson ’14 initially declared an English major at Franciscan but quickly switched to drama.

Bridget Anderson ’14 initially declared an English major at Franciscan but quickly switched to drama.

“There really is no drama department like Franciscan’s,” Bridget says. “We had to learn every aspect of drama: acting, directing, scenic design, theatre history, literature. We were involved in all the plays: on stage, behind the scenes, helping build the sets.”

Several professors suggested graduate school to her, but she said no. She graduated, moved to Boston, and took a corporate job, determined not to crack another book.

After two and a half years, she stepped back into academia, earning a master of arts in theatre history and criticism (dramaturgy track) from The Catholic University of America. Then, she began a doctoral program at the University of WisconsinMadison in the Interdisciplinary Theatre Studies Program.

“We’re encouraged to make connections with other departments to best support our individual projects,” says Bridget. “I do early modern theatre history, so I do a lot of Shakespeare. I work closely with the English Department. I’ve also worked with the History Department. One of my dissertation advisors is in religious studies.”

Bridget’s dissertation is on child actors in the 17th century, which includes “the importance of children in society and how little, innocent people can reflect truth.”

This year, she had an article published in Comparative Drama, titled “Kids at Play: Early Pedagogical Engagement With Shakespeare Through the St. Omers First Folio.”

“That was really exciting, to introduce a little taste of my dissertation and see the reaction to that.”

Next stop: more academia. Bridget would like to teach in a university: English or theatre or a little of both, hoping to encourage students to work in the entertainment world.

“Somebody’s got to create the good art,” says Bridget. “We’re all called to be creative. God is a creative God. We are all called to engage with the world in different ways. And for some of us, that’s through the entertainment industry through performance.”

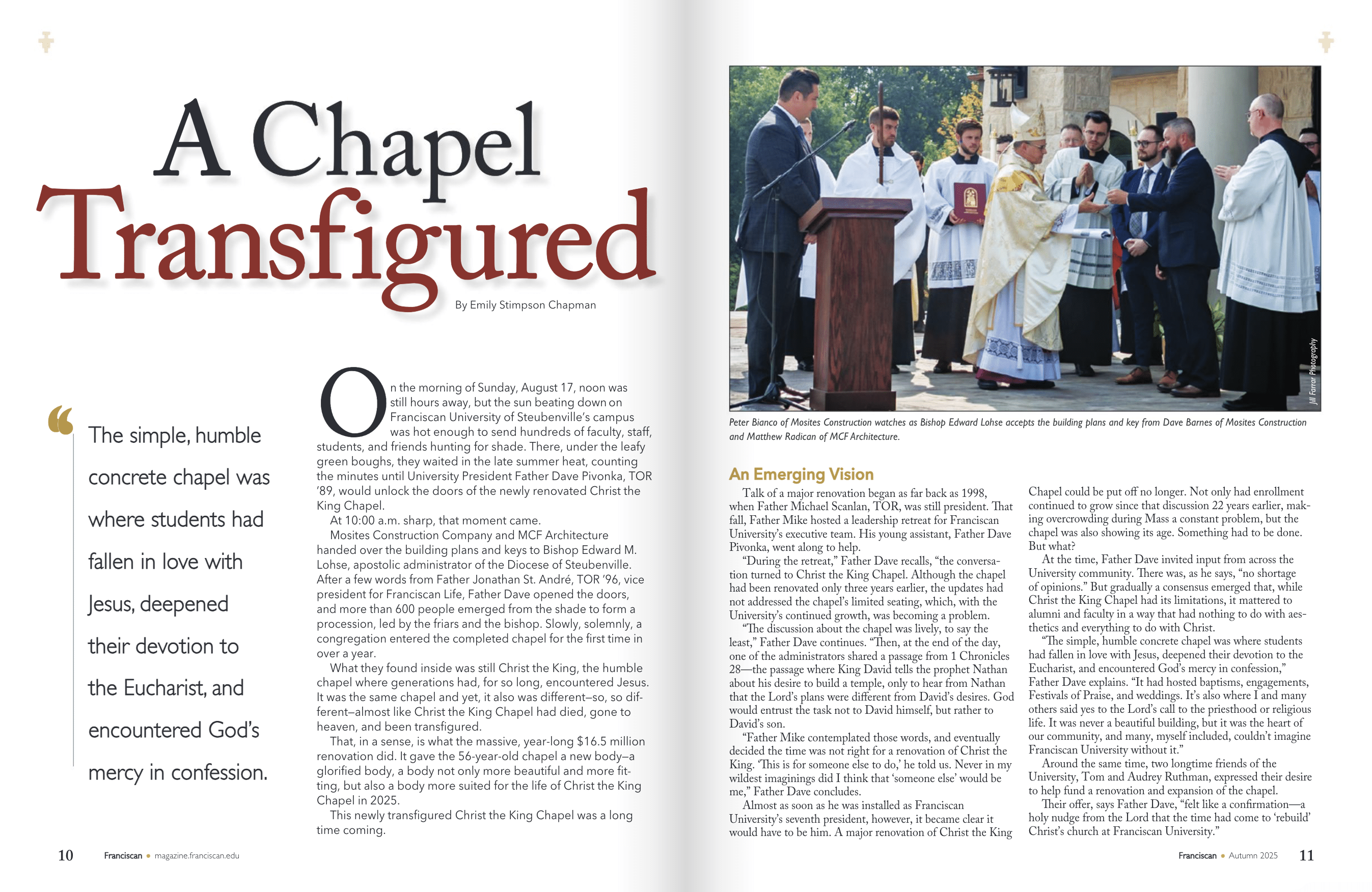

Daniel Davis ’13 is pursuing a doctorate in philosophy and education at Teachers College, Columbia University. At Franciscan, he studied history and philosophy and was in the Honors Program. He studied abroad twice, in the Austrian Program and at the University of Oxford at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies.

Daniel Davis ’13 is pursuing a doctorate in philosophy and education at Teachers College, Columbia University. At Franciscan, he studied history and philosophy and was in the Honors Program. He studied abroad twice, in the Austrian Program and at the University of Oxford at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies.

“Even at Oxford, I was able to engage in the conversation more meaningfully because of my honors classes that prepared me to do a deep dive into a text and then speak about what the author is trying to say,” he says.

After graduation he sold insurance for a few months, then got bored and quit “without a backup plan.” He started working as a substitute teacher and thought, I could do this. He earned his master’s in secondary education, then taught full time for nine years in schools in the Archdiocese of Boston.

But Daniel struggled with a question: What makes a Catholic school a Catholic school? What is authentic Catholic integration?

“I was recently married, and I told my wife, Casey, I needed to get a PhD. She said, ‘You mean after we’ve got kids, and we’re more financially secure?’”

But the Holy Spirit said now; and Daniel was accepted to Columbia, “the best program in the best school of education in the country.”

“We’re now living in Manhattan with our 9-month-old daughter. One year down, four more to go.”

Some of Daniel’s questions were provoked by the thought of Simone Weil, a French philosopher from the 1930-40s.

“I’m inspired by the questions she raises about education and the need for a person to be rooted, for moral agency and for human integrity.”

Daniel describes rootedness as a recognition of the dignity of the human person.

“There’s an ethical call to respect and cultivate the distinct roots of the human person,” in environment and place, in religion and traditions, and in intellectual and cultural heritage. “I don’t think we have a right to disregard that.”

Daniel’s work is specifically a philosophy of curriculum.

“I’m not telling schools how a rooted education should be implemented within their specific milieu. I can’t tell a community in Texas what a rooted education for them is. I have the questions they need to be asking and a more generalized framework.”

Daniel would like to teach at the university level.

“I have a deep interest in being a teacher of teachers. I’m hoping to have an impact on secular education as well as Catholic education, because rootedness is something all children need.”

Rosalia Palumbo ’22 didn’t get in to her first choice for college.

“I had my top school and my sister’s school. When I didn’t get in my dream school, I ended up going to Franciscan with my sister.”

It was supposed to be only one semester. And it wasn’t supposed to have that good of a science program.

“But it was really good,” says Rosalia. “The science program is strong, and the faculty are some of the best I’ve ever met. They trained us really well.”

Starting out as a biology major with an interest in genetics, she switched to biochemistry when that program began.

“It was a perfect fit.”

Now Rosalia is at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, pursuing a doctorate in chemistry.

“I had interned at Duquesne previously” in computational chemistry, “and I really enjoyed it,” she says.

She’s studying how DNA and RNA molecules “fold into specific shapes or structures, and how that can affect disease onset or disease treatment.”

The goal, she says, is to “identify genes that are altered in specific diseases. If we can find that the way it folds is contributing to how it’s expressed, hypothetically we could shift the fold to then either make more of the gene that’s helpful, or less of the gene that’s harmful.”

Rosalia hasn’t decided yet what she’ll do as Dr. Palumbo.

“Initially, I went to grad school thinking I wanted to do research. Now I’d like to review and edit research and articles for journals.”

Rosalia says, “I still rely on training, connections, and conversations I’ve had at Franciscan. I wish people who want to study science knew how good that program is.”

Seth Johnson ’18 MTS ’21 grew up in a devoutly Catholic family, but in high school, his own studies of Scripture led him to non-denominational Protestantism.

Seth Johnson ’18 MTS ’21 grew up in a devoutly Catholic family, but in high school, his own studies of Scripture led him to non-denominational Protestantism.

“My parents promised to pay for Franciscan University if I went there,” he says.

His parents encouraged him to put his objections to one of the theology professors, which led to several conversations with Dr. John Bergsma. In the first conversation, “he did a pretty good job, but I didn’t leave with, ‘Oh, wow, that changes everything.’ It was in the next meeting that he turned it up a notch. He started asking me questions.”

By the end of his freshman year, Seth came back to the Church and switched his major from psychology to theology.

“I knew as a sophomore that this is where my heart lies, and I knew I wanted to go on to do PhD studies. It was so thrilling to work through these issues. I knew I wanted to do this forever.”

Seth is studying systematic theology at Ave Maria University. His concentration is atonement theology—how Jesus’ dying saves us.

“We have all these models of the atonement, but which of these squares best with, for example, the sacrificial system of the Levitical priesthood or all the Old Testament sacrifices? How do they fit into the theology of the cross? And so many more questions.”

Seth eventually wants to teach theology at a Newman Guide school or a seminary.

To someone considering doctoral studies, Seth says, “It takes a level of dedication and sacrifice. You need to maintain your prayer life. God doesn’t want teachers who know a lot about him but don’t love him and don’t love their neighbor.”

Family has to be on board, too, says Seth, who is married to Maggie and has two young daughters.

And if you want to do doctoral work in theology, “spend your time in some ministry. Get into the lives of people and learn what questions grip them and learn what their minds and their hearts struggle with. It’s our job to craft intelligent answers from the heart of the Church for the questions of our age.”