“That we are all of the same intrinsic worth despite our variability—is a hell of an idea.”

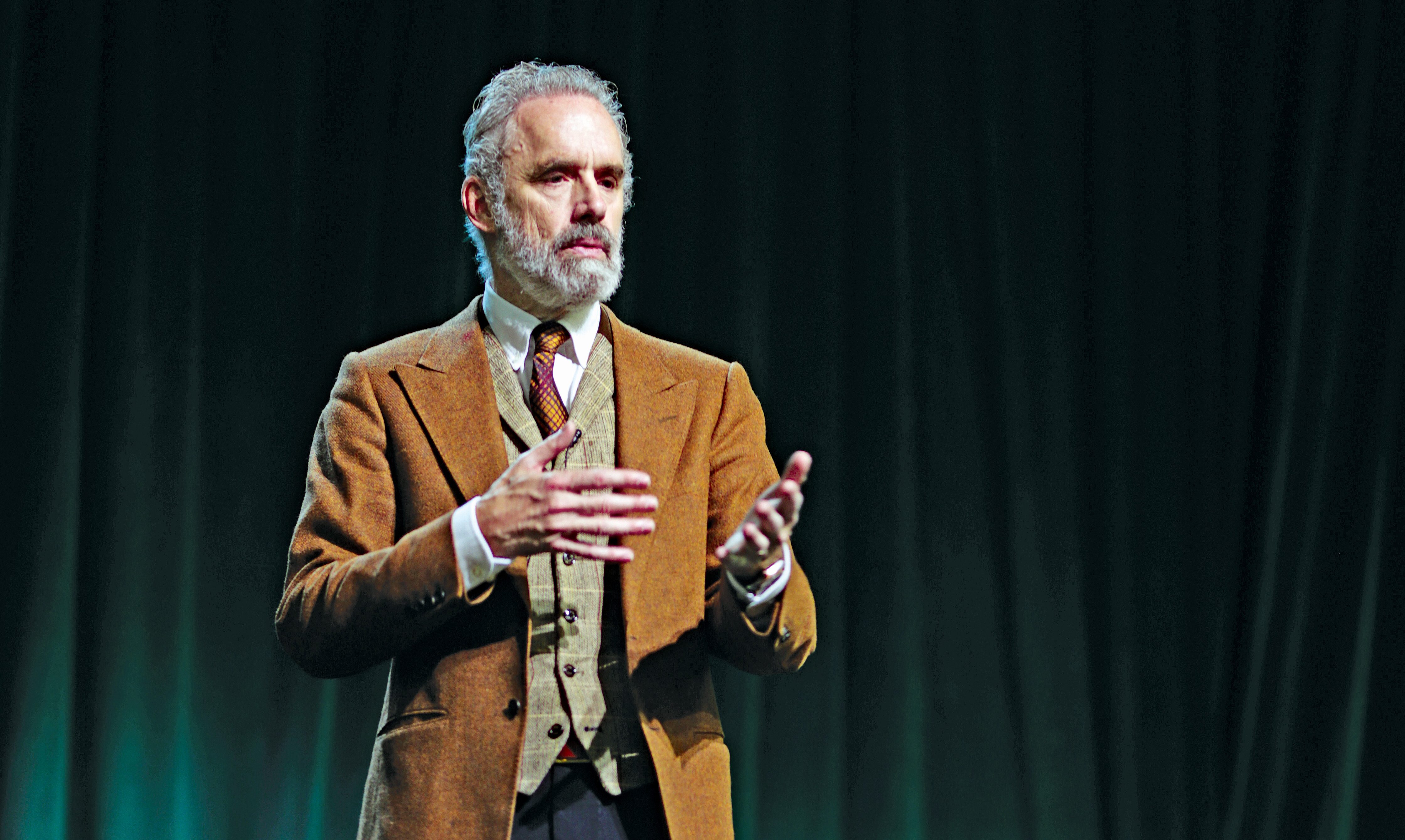

So said Dr. Jordan Peterson to a crowd of 1,500 Franciscan University students, faculty, staff, and guests the evening of April 4. “It’s absolutely amazing to me,” he continued, “that that idea ever obtained any purchase, anywhere, under any conditions.”

Peterson gave two talks: the first on the Bible as foundational to our cultural perceptions; the second, a conversation with University President Father Dave Pivonka, TOR, on being grateful in the midst of suffering.

Peterson has been a sailor, pilot, dishwasher, short-order cook, beekeeper, bartender, railway line worker, and more. He’s also a clinical psychologist, best-selling author, and global lecturer.

He’s a thinker, a searcher, an asker of hard questions. What he isn’t is Catholic.

So, when he approaches, for instance, the Bible, or suffering, he does it first as a psychologist and a scientist. Which makes for an interesting intellectual inquiry, even and especially for a person of faith.

“I had never heard Dr. Peterson talk before, so I didn’t know what to expect, but there was a lot of energy and excitement in the fieldhouse, and I enjoyed his discussion with Father Dave. It particularly struck me when Dr. Peterson referred to the bronze serpent in Exodus as exposure therapy, and when he said facing fears makes you braver, not less afraid. I appreciated the point made that suffering doesn’t go away, but if embraced, it can be transformational.”

– Senior Cecilia Engbert from Virginia

Peterson continued on the theme of intrinsic worth: “We sort of think of it as self-evident. That blinds us to exactly how miraculous that idea really is, and how unlikely it is. And yet it seems to be a fundamental necessity for the organization of the kind of social institutions that we would choose to inhabit.”

That notion comes from the Book.

“All books, particularly in the West, grew out the Bible.”

While the Bible is a collection of books aggregated over millennia, it has a narrative theme; a beginning, middle, and end; and a plot. In a “bizarre and interesting idea,” Christians take that a step further, positing that the Old Testament library of books has a plot, and implicit in that plot is the New Testament—“somehow present in the book before the events unfold.”

How this got plotted, said Peterson, is not thoroughly explained; for him it’s not enough to say that it’s the Word of God. He doesn’t seem to want a faith explanation.

At the same time, he points out that the logos is the ethic of the Judeo-Christian understanding of history: It’s the speech that calls order out of chaos, the Word that unites finite and infinite and finds embodiment in Christ. Logos is an “unbelievably profound, bottomless idea. To accuse the West of prioritizing logos doesn’t strike me as a damning criticism.”

Said Peterson, “If I’ve made any radical claims in my life, the most radical is that we can’t see the world except through an ethical framework. It’s actually technically not possible.” Postmodern types say your perception is nothing but your biases. But people of the Book believe there is such a thing as an ethic, “and that ethic is related to the integral worth of each individual.” That worth is “part of the religious presupposition in which our whole culture is embedded.”

Father Dave Pivonka then joined Peterson on stage for a conversation on suffering.

Suffering is central to the Christian experience, said Father Dave. “Redemption comes through suffering.” But our culture doesn’t deal with it very well, even though there’s something “beautiful and holy and salvific” about suffering, pain, and death.

Peterson turned to a story from the Book of Exodus. “I like to speak about things psychologically before I dare to speak about them religiously.” It’s a compelling story, he said, Moses leading the Israelites from Egypt and in the desert. The story begins with a tyrannical state, and the Hebrews longing for freedom through the spirit of God. And there’s a corollary to that: “We shouldn’t be subjects of tyranny if we’re children of God.” We accept that as obvious, that slavery is wrong. But “it’s not so bloody obvious,” said Peterson. It’s only wrong “if we’re sovereign individuals with some intrinsic worth.”

The Israelites escape tyranny and go to the desert. For 40 years. Said Peterson, “What kind of leadership do they have? It’s not that big a desert.” The Israelites are having a crisis of confidence, pining for the good old days of slavery. So, they complain. When God hears their complaints, “he sends poisonous snakes to bite them.”

They are in the desert, an “analog of hell,” and then because they lose their faith, hell gets deeper. “No matter how bad it is, there is always some bloody stupid thing you can do to make it worse.”

When Moses intercedes for them, God doesn’t answer by getting rid of the snakes. He tells Moses to make a bronze snake and raise it up on a staff so the Israelites can look at it. This response is “extremely surprising, and very interesting for a clinical psychologist.” In a clinical setting it would be called exposure therapy. “If I can find out what you’re avoiding and get you to confront it voluntarily,” you don’t get less afraid; you get braver. “It’s not like they get accustomed to what they’re looking at and they’re no longer afraid. What happens is they discover there’s a lot more to them than they thought.”

“I’ve heard Peterson speak before in small clips on YouTube, but hearing him speak in person, especially with Father Dave, was a great experience. There were parts of his talk that I genuinely sat back and was like, ‘wow, that’s an amazing analogy.’ I usually only do that during my theology classes.”

– Senior Ben Miller from Georgia

In the Gospel of John, said Peterson, Jesus compares himself to the serpent in the desert; a strange comparison on its face. But “what’s the most tragic story?” asked Peterson. “It’s the worst possible thing happening to the person who least deserves it. Christ is not merely innocent, he’s good; and not just good, he’s as good as it gets; and yet the tragedy of the Passion is the worst of all possible punishments visited upon the least deserving person.

Psychologically, said Peterson, our culture has put at its center this archetypal tragedy. “It’s as if we’re attempting to inoculate ourselves against the catastrophes of life.” But “the Crucifixion is not the end of the story. The end of the story is the Resurrection.”

Said Peterson, “In the psychotherapeutic milieu, if you get people to expose themselves to what they are terrified of, being terrified isn’t the end of the story. Recovering is the end of the story.”

Father Dave took it a step further: “When we look at the cross, we always see Jesus there. Our businesses are similar: People bring us their brokenness. I believe in a God who can transform that.”

Jesus is present in the midst of the suffering, said Father Dave. “In the midst of my brokenness, suffering, and pain, he reminds me that I’m loved.” In the Christian mystery of suffering, “God enters the messiness rather than just fixing it. He enters it and takes it on himself and transforms it.”

The pathway to less suffering, said Peterson, is through suffering. “How do you make it worse? Run away. How do you make it better? Confront it.”

Watch “You Probably Should Have Read the Bible” and “This Lesson From the Bible Will Make You Unstoppable” at franciscan.edu/peterson.