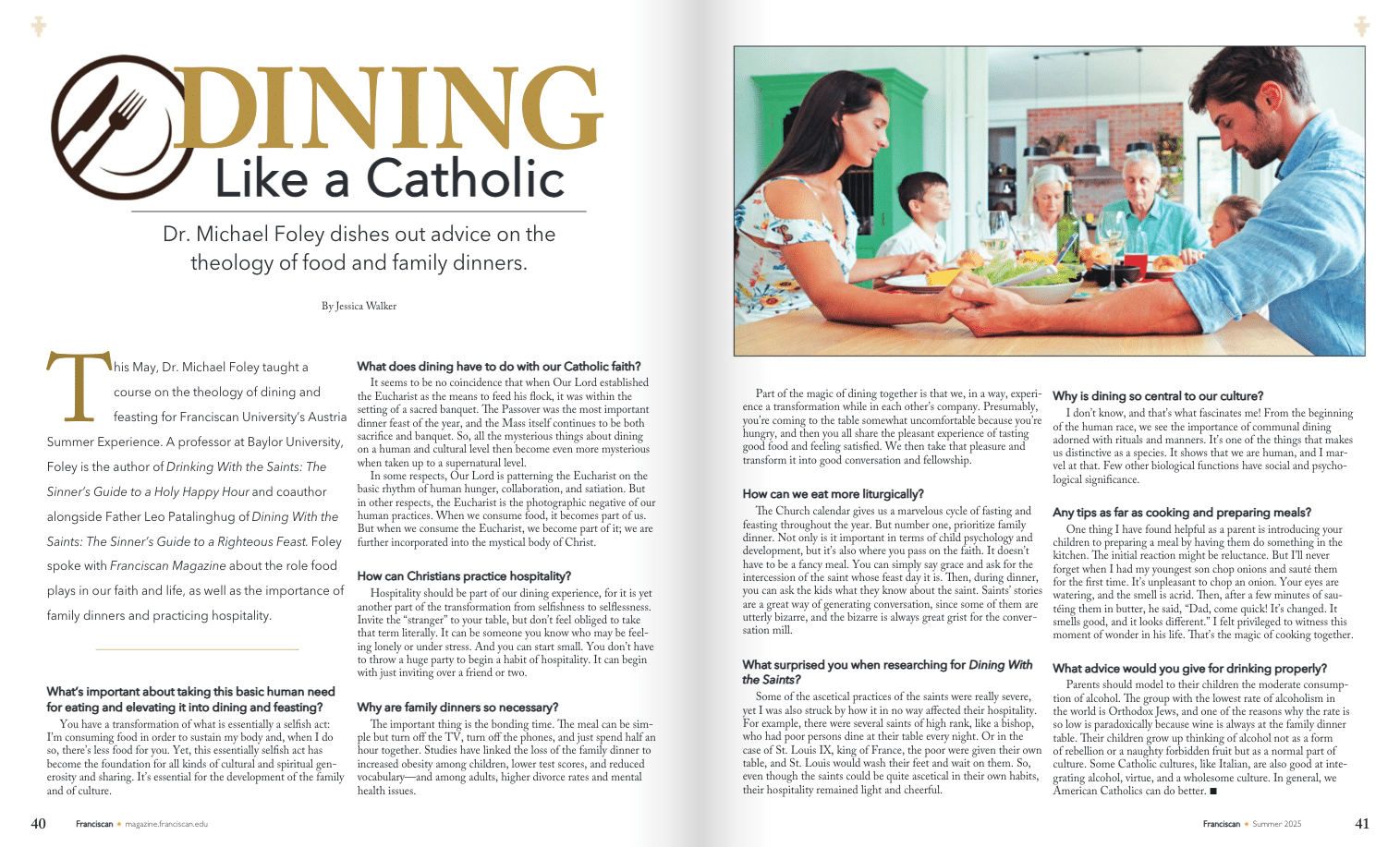

This May, Dr. Michael Foley taught a course on the theology of dining and feasting for Franciscan University’s Austria Summer Experience. A professor at Baylor University, Foley is the author of Drinking With the Saints: The Sinner’s Guide to a Holy Happy Hour and coauthor alongside Father Leo Patalinghug of Dining With the Saints: The Sinner’s Guide to a Righteous Feast. Foley spoke with Franciscan Magazine about the role food plays in our faith and life, as well as the importance of family dinners and practicing hospitality.

What’s important about taking this basic human need for eating and elevating it into dining and feasting?

You have a transformation of what is essentially a selfish act: I’m consuming food in order to sustain my body and, when I do so, there’s less food for you. Yet, this essentially selfish act has become the foundation for all kinds of cultural and spiritual generosity and sharing. It’s essential for the development of the family and of culture.

What does dining have to do with our Catholic faith?

It seems to be no coincidence that when Our Lord established the Eucharist as the means to feed his flock, it was within the setting of a sacred banquet. The Passover was the most important dinner feast of the year, and the Mass itself continues to be both sacrifice and banquet. So, all the mysterious things about dining on a human and cultural level then become even more mysterious when taken up to a supernatural level.

In some respects, Our Lord is patterning the Eucharist on the basic rhythm of human hunger, collaboration, and satiation. But in other respects, the Eucharist is the photographic negative of our human practices. When we consume food, it becomes part of us. But when we consume the Eucharist, we become part of it; we are further incorporated into the mystical body of Christ.

How can Christians practice hospitality?

Hospitality should be part of our dining experience, for it is yet another part of the transformation from selfishness to selflessness. Invite the “stranger” to your table, but don’t feel obliged to take that term literally. It can be someone you know who may be feeling lonely or under stress. And you can start small. You don’t have to throw a huge party to begin a habit of hospitality. It can begin with just inviting over a friend or two.

Why are family dinners so necessary?

The important thing is the bonding time. The meal can be simple but turn off the TV, turn off the phones, and just spend half an hour together. Studies have linked the loss of the family dinner to increased obesity among children, lower test scores, and reduced vocabulary—and among adults, higher divorce rates and mental health issues.

Part of the magic of dining together is that we, in a way, experience a transformation while in each other’s company. Presumably, you’re coming to the table somewhat uncomfortable because you’re hungry, and then you all share the pleasant experience of tasting good food and feeling satisfied. We then take that pleasure and transform it into good conversation and fellowship.

How can we eat more liturgically?

The Church calendar gives us a marvelous cycle of fasting and feasting throughout the year. But number one, prioritize family dinner. Not only is it important in terms of child psychology and development, but it’s also where you pass on the faith. It doesn’t have to be a fancy meal. You can simply say grace and ask for the intercession of the saint whose feast day it is. Then, during dinner, you can ask the kids what they know about the saint. Saints’ stories are a great way of generating conversation, since some of them are utterly bizarre, and the bizarre is always great grist for the conversation mill.

What surprised you when researching for Dining With the Saints?

Some of the ascetical practices of the saints were really severe, yet I was also struck by how it in no way affected their hospitality. For example, there were several saints of high rank, like a bishop, who had poor persons dine at their table every night. Or in the case of St. Louis IX, king of France, the poor were given their own table, and St. Louis would wash their feet and wait on them. So, even though the saints could be quite ascetical in their own habits, their hospitality remained light and cheerful.

Why is dining so central to our culture?

I don’t know, and that’s what fascinates me! From the beginning of the human race, we see the importance of communal dining adorned with rituals and manners. It’s one of the things that makes us distinctive as a species. It shows that we are human, and I marvel at that. Few other biological functions have social and psychological significance.

Any tips as far as cooking and preparing meals?

One thing I have found helpful as a parent is introducing your children to preparing a meal by having them do something in the kitchen. The initial reaction might be reluctance. But I’ll never forget when I had my youngest son chop onions and sauté them for the first time. It’s unpleasant to chop an onion. Your eyes are watering, and the smell is acrid. Then, after a few minutes of sautéing them in butter, he said, “Dad, come quick! It’s changed. It smells good, and it looks different.” I felt privileged to witness this moment of wonder in his life. That’s the magic of cooking together.

What advice would you give for drinking properly?

Parents should model to their children the moderate consumption of alcohol. The group with the lowest rate of alcoholism in the world is Orthodox Jews, and one of the reasons why the rate is so low is paradoxically because wine is always at the family dinner table. Their children grow up thinking of alcohol not as a form of rebellion or a naughty forbidden fruit but as a normal part of culture. Some Catholic cultures, like Italian, are also good at integrating alcohol, virtue, and a wholesome culture. In general, we American Catholics can do better.