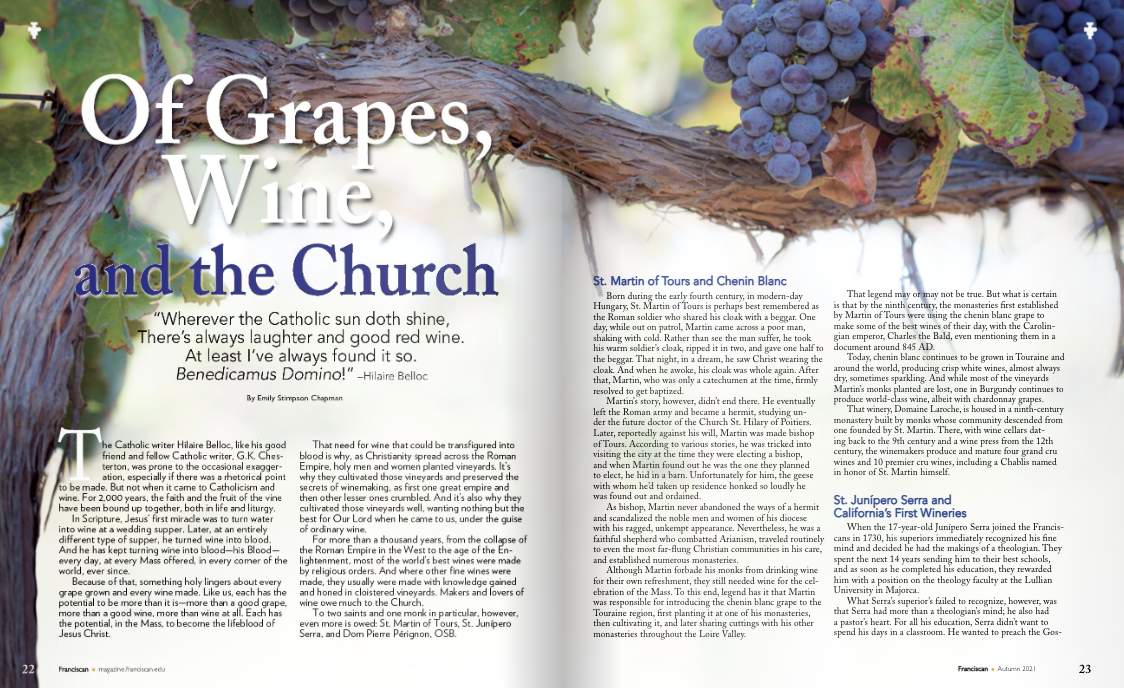

From fighting cancer and infections to ecological management to building new pharmaceutical ventures, Franciscan University faculty and students are leading and developing new research in the life sciences. And, whether logging observations in the field, synthesizing molecules in the lab, or presenting published papers at conferences, they are witnessing to the integration of faith and reason in the scientific community at large.

Streams, Salamanders, and Stewardship

A two-foot long salamander bearing the name “hellbender” might make some squeamish. But biology professor Dr. Eric Haenni and his students celebrate every time they encounter one of these large amphibians.

“Many of our local streams have relatively low biodiversity, as erosion and acid mine drainage have taken their toll. But the hellbender finds ways to survive even in places where we didn’t think they could,” Haenni says.

In 2014, the Jefferson County Soil and Water Conservation District invited Haenni to study hellbenders on their land. A major driver for this research was developing best practices for agriculture to help increase production while protecting local streams.

![]()

“We want to find ways for farmers to be profitable while also taking ownership of the environment and protecting the beauty of our biodiversity. The Catholic Church speaks to sustainability but not in spite of humanity,” he emphasizes. “We help students understand everyone is called to utilize resources in a way that is harmonious with human dignity. Figuring out how that works on the ground is a case-by-case, community-by-community discussion. But they are incredibly important discussions.”

Thanks to a grant secured in 2017, a dozen artificial habitats were constructed and are being deployed in local waterways. These simulate the rock formations the salamanders like to live in, and researchers can access and collect data in a less invasive way than was previously possible.

“We have been building relationships with local landowners to get these shelters in our area streams. We are getting a better sense of where these populations are and what areas they seem to thrive in,” Haenni says.

Franciscan students take a leading role out in the field.

“We encourage a ‘get your hands dirty’ approach. They are out in the middle of streams with waders on, taking measurements and watching the ecosystems. I also encourage them to take time and just ‘be’ and enjoy what God created.”

This project also gives students experience with tools they need in the industry, Haenni says.

“This research trains them in universal techniques for habitat and stream assessment. Local students who wanted to stay in the area after graduation were prepared to get jobs nearby in scientific fields due to their time here. Furthermore, a major goal of the department is to get students on a publication. This not only helps their résumés but also allows them to evangelize out in the scientific, peer-reviewed community.”

Invasive Species and Dominion Over the Earth

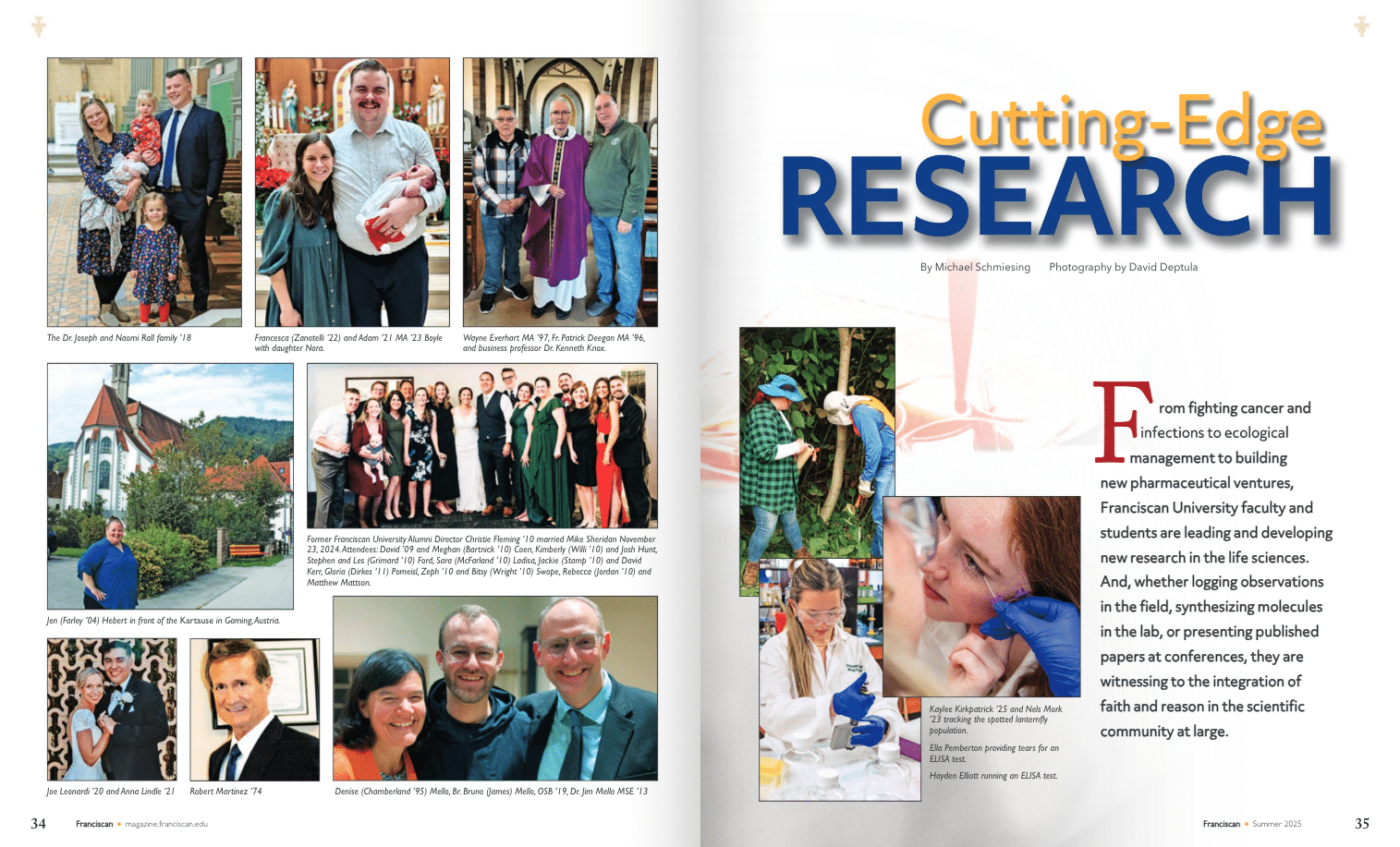

While Haenni hopes to see more hellbender salamanders in the Ohio Valley, Dr. Christopher Payne, assistant professor of biology, and his students seek to understand a less welcome creature, the spotted lanternfly.

While Haenni hopes to see more hellbender salamanders in the Ohio Valley, Dr. Christopher Payne, assistant professor of biology, and his students seek to understand a less welcome creature, the spotted lanternfly.

“We caught one lanternfly in 2021, the third ever in Ohio. In 2022, 31 were caught, and then in 2023, it went up to 8,600. Last year, 207,000! The 2025 estimate for our plots we are observing is 5 million,” Payne says.

The spotted lanternfly is native to China and was first sighted in the U.S. in eastern Pennsylvania, apparently arriving by shipping container.

“These bugs are technically ‘planthoppers’ and can’t actually fly,” Payne says. “They climb as high as they can, then jump. But what they do really well is grab onto cars and trains. They can withstand more than 60 mph of wind, so they can get carried a long way quickly.”

In October 2020, Payne and then student Melody Vetrovec ’23 started evaluating the local environment.

“We knew the invasion of the lanternflies was inevitable,” he explains, “so we decided to document local plants and insect life before they arrived. This would set us up to conduct a long-term study to look at the ‘before’ and ‘after’ and measure the impact this species has in our area.”

Lanternflies can damage woody plants, with grapevines and fruit trees most at risk.

“Even if the lanternflies don’t kill a tree, they can potentially reduce its ability to store nutrients, stunting its growth,” Payne says. “We can’t currently stop the lanternflies, but our project is gathering important information on their spread. This helps us better understand them and exercise the dominion God has entrusted to the human race. We want to help counter the threat they pose to human life through reduced biodiversity and damage to agriculture.”

Their work has been noticed and has received multiple federal grants. Payne says they have conducted 15,000 surveys over 20 monitoring sites, which is more than just about any non-governmental organization in the Eastern U.S. Fifteen students have participated on this project over four years, including seven who have won summer internships through the Franciscan Institute for Science and Heath (FISH) summer research program.

“The students are getting hands-on experience in a relevant, long-term research project that allows them to advance not just in knowledge but also in their academic and vocational journeys,” he says.

Two student-authored articles have been published in peer-reviewed journals, with three more on the way. Vetrovec is now a lab manager at the Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. And this research experience also helped Alvio Barbaretta ’24 land a master’s degree position at Florida Gulf Coast University, Luke Kerner ’25 get a state-government conservation job for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and sophomore Colin Mahon win an invasive species internship in Wisconsin.

Fighting Cancer, Healing Scars

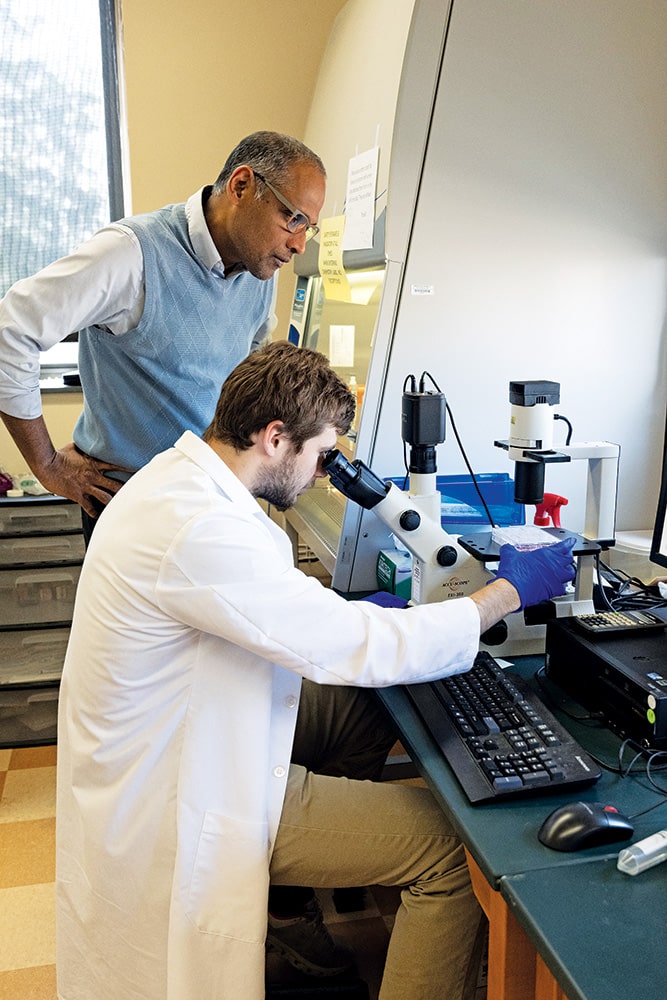

Biology professors Dr. Joseph Pathakamuri and Dr. Daniel Kuebler set their sights on finding alternative treatments for cancer besides radiation and chemotherapy. And, together with their students, they have identified a promising new and less invasive way to treat breast cancer.

Biology professors Dr. Joseph Pathakamuri and Dr. Daniel Kuebler set their sights on finding alternative treatments for cancer besides radiation and chemotherapy. And, together with their students, they have identified a promising new and less invasive way to treat breast cancer.

“Cancer cells divide more rapidly and have different cellular and electrical properties than normal cells, making them more susceptible to disruption by specific stimuli,” Pathakamuri explains. “We have found success using low energy oscillating electrical fields to disrupt cancer cell division. By exposing the cells to these fields, and periodically changing their direction and intensity, we can stop the replication of cancerous cells without impacting the health of normal cells.”

Franciscan students are actively experimenting with breast cancer cells in the lab.

“Working with a team of collaborators, we designed specialized equipment from the ground up to administer the electrical fields. Our students really took the lead in using the machine and have seen great success in slowing or stopping the growth of cancerous cells,” Pathakamuri notes. “The relationships we’ve built in this project and the real-world experience it has given our students have shown them how research is connected to clinical practice, which will help them in their careers and vocations.”

Using the custom-built machine, which is smaller than a laptop, they also tested its effects on scar tissue formation.

“To our surprise, we found that applying electrical fields also slows down the development of scar tissue in a tissue culture model,” Kuebler says. “This could help patients who suffer from excessive scar tissue formation after radiation, operations, or serious wounds. Some of our students have submitted an abstract to present these findings at the 2025 American Radiology Conference.”

Kuebler and Pathakamuri express gratitude for their collaborators from Prisma Health Cancer Institute and Clemson University who made this project possible.

“Dr. John O’Connell, a radiation oncologist and member of the Catholic Medical Association, and Jason Henderson, a biomedical engineer, helped us get this project started,” says Pathakamuri.

Mysteries of Immunology

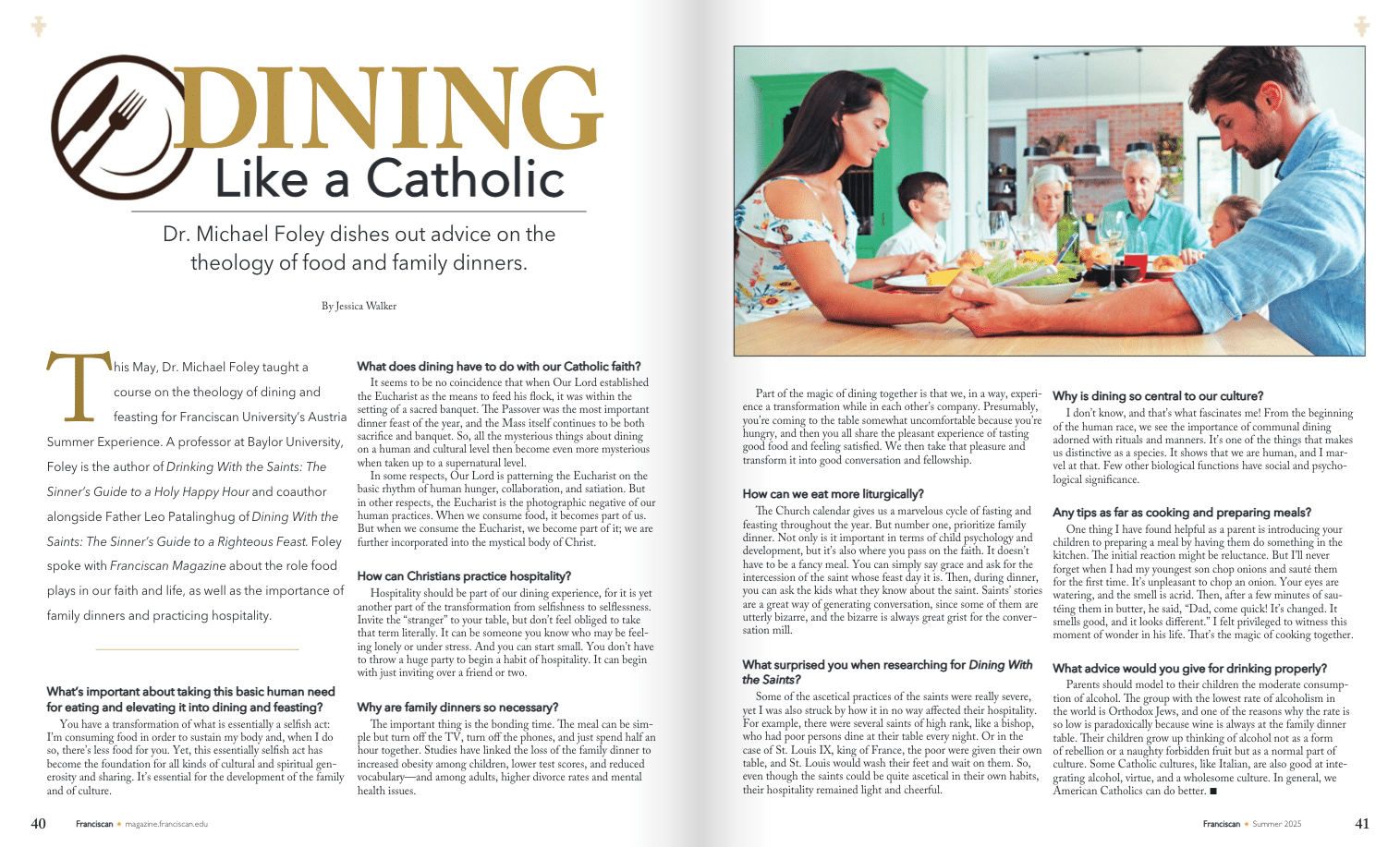

Biology professor Dr. Kyle McKenna and his team of students have been conducting a multi-year longitudinal study to better understand the workings of the human immune system.

Biology professor Dr. Kyle McKenna and his team of students have been conducting a multi-year longitudinal study to better understand the workings of the human immune system.

“We were seeing very high concentrations of anti-SARSCoV-2 IgG antibodies in the blood of people who had received a COVID-19 vaccine or who had resolved SARS-CoV-2 infection. Normally, that means people are safe from future infection, but we observed people were still getting sick,” McKenna says.

While focusing on the infamous pandemic-causing coronavirus, the implications of this research can open doors to developing more effective vaccines and providing more effective antibody testing to evaluate protection from reinfection.

“We started taking a serious look at antibodies back in the early days of COVID when we were trying to figure out how close the campus was to herd immunity. There were lots of people who were asymptomatic who had high levels of IgG antibodies in their blood indicating they had been infected,” he says. “While we were able to figure out who had been infected or vaccinated through COVID antibody testing, we quickly realized these tests were not providing an indicator of who was ‘immune’ from subsequent viral infection.”

Last year, the team moved its focus from IgG antibodies in the blood to studying IgA antibodies in the “mucosa,” the membranes of the mouth, nose, and eyes, McKenna explains. These areas are where airborne viruses enter the body, and therefore, an immune response here represents a “front-line defense” against infection. IgA are the predominant antibody in the mucosa, with four binding sites for viruses. IgG only have two; thus, IgA antibodies are more effective at neutralizing viruses. By evaluating the concentration of IgA antibodies in blood, tears, and saliva, their current research indicates compartmentalization of the IgA response.

In this study of multiple volunteers, they have observed that having IgA antibodies in blood doesn’t assure IgA antibodies will be in the tears or saliva to stop viral infection in the eyes, nose, and mouth. How IgA antibody concentrations change over time in these front-line areas may identify who is more susceptible to infection. This research reveals that what it means to be “immune” is more complicated than previously thought.

Beyond the practical applications of this research, this project has Franciscan students going out into the broader scientific community.

“We published two papers in the Linacre Quarterly, the journal of the Catholic Medical Association, and presented our research at the annual meeting of the Ohio Academy of Science,” McKenna says.

These experiences gave Franciscan students not only a chance to share their data with the scientific community but also an opportunity for apologetics and evangelization, as the McKenna laboratory’s COVID-19 antibody tests were intentionally designed without any materials derived from aborted-fetal cell lines.

“We were very pleased to provide both an effective and ethical alternative COVID-19 antibody test. The nature of this project leant itself to living out the Catholic faith in our science,” McKenna says.

Building the Building-Blocks of Medicine

Franciscan students also do rigorous work in the chemistry labs, synthesizing and purifying all sorts of compounds with specially designed reactions and techniques. Dr. Jeff Rohde, chemistry professor, and Dr. Mira Kanzelberger, senior research scientist, are looking to employ these well-trained students in a new business that would help the pharmaceutical industry develop safer and more effective medicines.

“We have already had students whose work has helped in the development of lifesaving drugs. Daniel Gray ’19, Chris Finocchio ’18, and Peter Rainwater ’19 MSE ’25 contributed to the process chemistry review and approval of fexinidazole, an oral pill that cures African sleeping sickness,” Rohde says.

Discovering and vetting new medicines is a very time- and labor-intensive process that starts with preparing and testing molecules with promising properties.

“This level of development helps lay the foundation for a new medicine. Much of this work has been outsourced overseas, but our students are competently synthesizing these exact compounds needed for drug discovery. This trains them in skills crucial for organic chemistry, but it is also creating compounds valued by companies that are searching for new medicines,” notes Rohde.

The more complex molecules Rohde and his students target have shown promise in creating drugs that are both more effective and safer.

“Drugs developed from larger, ‘two-dimensionally shaped’ and weaker binding molecules can have a higher possibility of interacting with the body in a way that was not intended. You could almost say that, because they are flatter and weaker binders, they ‘fit’ in places where they don’t belong. We are synthesizing tight binding, core compounds as well as novel ‘3D’ compounds to help buyers more quickly develop new potent and effective drugs with fewer side effects,” Rohde says.

“We’ve done a lot of research with Duquesne University optimizing the ‘3+2’ chemistry, which is one method we use to assemble molecular rings and other three-dimensional molecules. We have also focused on preparing azaindoles, a known core in currently marketed drugs, and have variations that show real potential for future development.”

The startup has over 50 compounds available for sale and has already seen interest from the pharmaceutical industry. Profits will be reinvested in Franciscan’s Chemistry Program research initially and then expand to support additional research and other initiatives.

“Over the past 15 years, our students have built a reputation through work in internships at places like AbbVie, Eli Lily, and the Cleveland Clinic Center for Therapeutic Discovery, as well as their impressive studies at universities like MIT, Michigan, and North Carolina Chapel Hill, where they have earned PhDs before launching successful careers in both the pharmaceutical industry and academia,” says Rohde. “Their consistent witness to integrity has drawn attention and given this effort credibility. In retrospect, you can see the finger of the Holy Spirit laying the groundwork to make this effort possible.”

For more information about student research opportunities and to support the sciences at Franciscan University, visit institutes.franciscan.edu/fish.